Recently, Tim Urban, a blogger, writer, popularizer of science and simply an excellent storyteller, came to Liv Boeree's podcast (Igor Kurganov also did not miss such a meeting). One of his favorite topics is the fight against procrastination, and in the podcast, Tim talked about the mechanics that allow him to work effectively. We decided to translate this piece (and a couple more), because Tim's methods can clearly be useful for poker players. We also added a summary of Urban's sensational lecture on procrastination as part of the Ted Talks project.

Liv: So, how's the book writing going?

— I'm on chapter 17 of 17.

Liv: Wow!

— But that chapter is about turning into about a quarter of the book. Is it like the last book, where it was like exponentially growing? That last chapter was like, no, no, that was a much crazier situation. This is just the last chapter, which I'm actually calling "The Futures" because it's like we don't know which of the futures. There's not one future. And it turns out there's a lot of stuff to say about the future, and I'm trying to limit myself; I can't go too crazy because I've already written so much getting up to the present and through the present, from the big bang.

But, uh, I'm trying—I was like, okay, I'm gonna do little mini-explainers—but there's just a lot of things to explain and talk about. AI part one, which is kind of up to potential AGI, like kind of where we are now plus three years. And then there's all the different trends in transportation—there's like five different things to discuss there. There's humanoid robots, cultivated meat, as you guys know all about, there's all the different things in biotech and health span, like CRISPR and transcription factors and bioelectricity, and all of these things going on there. And then there's energy infusion, right, and space, brain-computer interfaces, brain-computer interfaces, just longevity, like the more moonshot biotech stuff.

And then there's the second part of AI, which is, you know, ASI. And you know that's the thing you can't bring up early because once you bring that up, nothing else seems like it matters. So, you have to talk about everything else first and then say, oh by the way, if we actually get to this other thing—super intelligence—none of the other stuff really is that important.

Igor: So, is that the ending for your book? "By the way, all the things I wrote might be different."

– No, I finish with that, with ASI, and that's the last part of the future because that's again—you can't, you can't—nothing is exciting after you've talked about ASI.

Igor: But also, it's I find it so hard to think about what true super intelligence would lead to in our current world. And I think that's actually in part why so many people kind of dismiss it or don't have any belief in it because it's just so difficult to imagine what it would be like to have 1,000 like remote workers constantly available with a 210 IQ or something, just like working on, yeah, like people in a room basically with a computer sitting there and doing it.

– It's like a whole other category, and everything else is part of one category, and that's this. It's like a bunch of monkeys are living in a little civilization, and they're talking about different ways to harvest bananas and different ways to grow trees, they can swing from different kinds of branches, and all that. And then it's like, oh, we're also doing this other thing in these certain labs; we're inventing humans. And it's like, well, that seems like it is actually more important than all of these things combined.

And that's that's a little bit—it's like, but we also don't know yet if that's actually gonna play out the way that we may maybe we won't get there for some reason, or maybe it'll take a lot longer.

Liv: People always talk about having good positive incentives for yourself, thinking of the reward, and so on. I think most of us actually just respond better to negative incentives—like we need the stick.

Igor: Especially if you have a cushy life, relatively speaking, to many other people. Right, if you're comfortable, then a bit more carrot is like, oh man, I've just had a carrot. And also, I can't enjoy a carrot if I'm in the middle of my project and I'm like, it's just going to be hard for that to work.

— When you're doing a blog post, there's a huge carrot, which is about to publish it—so exciting, right. And there's just not going to be that for this book. To answer your other question, like how would a grown-up do this without a carrot or a stick? The answer is that you can't think about the big project you're not working on your book right. You just can't.

What you're trying to do is, I have a chess timer on my desk, and you know, 6:30 is stop time because that's when I'm going to put the baby to bed, and that's it. So, I'll usually sit down around 10:00 or 10:30, and that's about eight hours. I will set four hours to the work side of the timer, the white pieces, and I'll set four, four and a half, or four and twelve, whatever the exact number is, on the other side—whatever the remainder is. When I'm working, that work side is ticking down. If I go to the bathroom, if I stop to play with the baby, if I take a phone call, if I check my text, I hit it, and the other side starts to tick up.

Liv: Wow.

— The rule is, I must get the work side to the bottom before the other side. Ideally, it's also that when I look at that, I'm not allowed to go over four hours, which is an important part of it. Because then it's an incentive to say, you know, if I get up and I can just get to work, I can knock this out by like 2 p.m. and be free all day. It's getting back into that teenage psychology of like, I don't want to go to school, but I have to, and then, oh, school's out—like saved by the bell. I'm done; I'm free; I don't have to think about that until tomorrow. I'm free.

I think I had the wrong psychology with the first book, which is I was my own boss, and I'm like, I have all day; I make the rules; I'll work when I'm ready. But I'm going to do this huge amount of work, and I would end up doing way less than four hours. Four hours is a huge day, but it's also only four hours. Let's say you have 16 waking hours in the day, so it's this crazy thing where if you're doing it right, you can make this four hours a day compile like crazy. It's also only four hours, so you have 12 free hours a day. Before, somehow I was getting way less than that done a week, and I felt like I had no free time.

Liv: How accurate is your tapping in and out?

— I try to always police myself because if I'm going to be a bit dishonest and I have to hit the other timer, I'm like, what am I doing? Why am I hitting that stop work? It's like you have to actually be like nope, I'm moving over to this timer—is it right? Why am I moving over to that timer? Like 11 a.m., it makes no sense right now. But if I do catch myself where I'm like, oh, I just wasn't using the wrong timer for a half hour, I'll just reset the times because I want to get it right, and I don't want to cheat it at all. I want to make sure I get those four hours in.

Liv: I've never heard this before; it's brilliant.

— It really works well because there are two parts to it. One is that four hours has to tick down, and that's automatically a productive day. But the other part is, I don't want the other side to tick down. I'm realizing there's a cost to the procrastination time, which is that okay, I have this precious time also to be doing. I could go out and do something; I could, you know, do my shallow work; I could actually get through my emails—whatever it is that's also valuable. Am I using that well? Like, I want to be using both of those well.

Systems basically are like just systems to help me have a not-crazy day. Not these wild days when I wrote 4,000 words and had like this magical day—none of that. Just a solid Wednesday: got some research done, wrote a few paragraphs, rejiggered the outline a little bit, took four hours, moved on. That's the unit of like, book total finished in two years.

Liv: How is your attitude towards working and being an adult changed since you became a dad?

— Well, I would like to say I thought and I hoped that it would change me fundamentally, where I'm just more of a grown-up now. I don't think I am. Maybe that's when you have like a seven-year-old and you're actually really parenting someone; maybe that kicks in. What it has done is just regimented my time a lot more. I mean, there's no possibility for me to just say, "I'm gonna get going on my work at 10 p.m. tonight and work till three," because I'm on a schedule that often has me waking up with her first thing in the morning. It's just totally different.

I'm always stopping at 6:00 or 6:30 because I put her to bed every night, so that is it. Just basically, it's just constrained my time a lot more. I have much more of a normal grown-up schedule, and I have to. You two don't have to because you two are just like, I'll sometimes be over here and I'm just chatting till two in the morning, and I'm like, my alarm is set for seven.

The point is, if I'm waking up at seven two or three days a week, my circadian rhythm can't go back and forth like now. I'm just gonna suddenly be someone who needs to go to bed before midnight, or I'm gonna be exhausted, which I never was. I was always at like a two or three a.m. to 10 or 11.

Liv: Have you had any all-nighters since you had your daughter?

— Like zero. It's funny; I pulled an all-nighter the day this got published. You know, getting the website ready, getting into the promo ready, all the little things—of course, there's glitches at the last second.

Liv: So, in your 2014 post on the importance of picking a right life partner, there's a quote in it which said, "If it were me, I would rather adopt children with the right life partner than have biological children with the wrong one." How now that you've had your own child and you've got a second on the way, do you still adhere to that statement?

— If you're with the right person, it's like, okay, let's together work on coping with the fact that we're not going to have biological children. Let's talk about it; let's make a bunch of philosophies around it together, and that's it. Now, let's just joke about the fact that we have these hilarious adopted children that we love and raise them, and everything's great. And that's fine. It's like, if you put me in that situation, once you get over the disappointment, and then you adjust, and life is great. If you're married to the wrong person, everything sucks all the time, right? Including for the biological children growing up in a household with an unhappy marriage. It's not fun.

Yeah, and of course, it can be really unhappy; it can be abusive, or it can just be like you really hate each other. That's obviously just terrible. But even just like you like your friends a lot more than you like this person—like, they're fine; you get along with them fine; you're somewhat compatible—but like you don't really like spending time with them very much, and you don't really like talking to them that much. And when you're with your friends, you're like, "Ah, my people." And then you leave, and it's just the two of you getting in the car heading home, and you're kind of like, "Yeah."

Liv: You call it the traffic test.

– Yes, imagine that a husband and wife are driving home, talking. And then bam, suddenly they get stuck in a traffic jam. That means they have to talk longer! And there are couples who won't be upset at all in this situation. And there are those who will be terribly annoyed.

I have friends with whom I really enjoy spending time, just chatting. Sometimes they give me a ride home – I would stand in 10 traffic jams just to spend an extra hour with them. And I can't imagine how you can live (!) with a person who doesn't evoke such emotions in you. And this is not a high bar, you must admit. After all, I really do have this with a few friends. So how can it not be with my wife, with whom I spend 10 times more time?..

Igor: . I want to put a caveat on it, so like I agree, and I think that we're lucky to have found a partner in each other to have to share that with, and the same applies to you and Tanis as well. And like, we often look to you at that, but I think that relationships can be like extremely happy relationships without that characteristic, actually.

– I can agree with that caveat, which is that really what I was talking about with the traffic test was my criteria, right, for my personality.

I happen to be someone who the thing I love about all my friends most is I just love brain-playing with them; I love talking to them, laughing, talking, analyzing, whatever it is. And so for me, and it really was what I think was encouraging people to do in that post, was like come up with your criteria. You should have them. And then, uh, you know, you need to know what you're both selecting for and also what you're not selecting for. Something's not a deal-breaker; then don't let that put that aside. Like, that's a nice to have, not a need to have. The traffic test was a need to have for me. I just know myself; if I was at a dinner with a couple of friends and my wife, and we're all having a great time talking, and then we get in the car and I'm like, "Uh, now I'm bored," I'm not gonna be happy.

Liv: I like to finish up these quick episodes with rapid-fire predictions.

— Likelihood that you'll write another hundred thousand plus word book in your lifetime:

— 90%.

— Likelihood that some kind of external intelligence, like God or a simulator, exists:

— 10%.

— Likelihood that there is life advanced enough to communicate with us in the galaxy:

— 70%. It's a big galaxy.

— Likelihood you'll be using a brain-computer interface by 2050:

— 68%.

— Likelihood you'll live to the age of 200:

— 12%.

— Age of 5,000:

— 2%.

— Likelihood that we make it as a civilization up to the year 2075 and pass it through AI, ASI, all of that:

— 80%.

Tim Urban: "Let's Look Inside the Head of a Procrastinator"

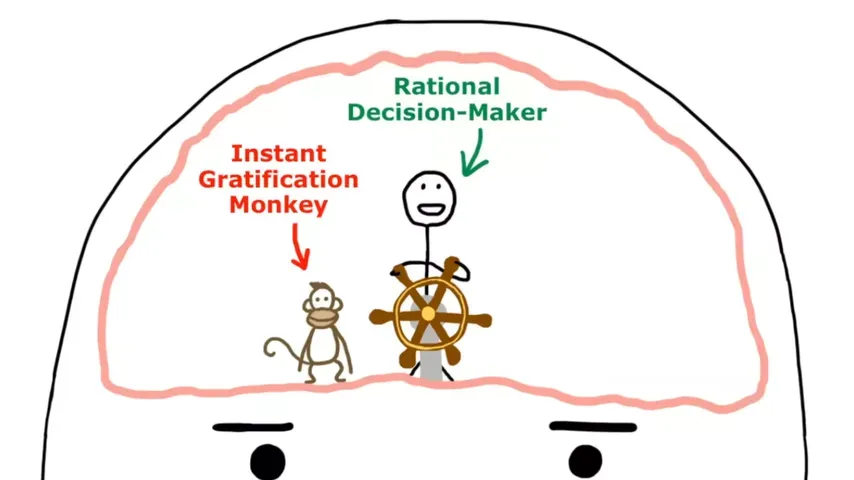

This is how I imagine my brain:

Both brains have a Rational Decision-Maker in them, but the procrastinator's brain also has an Instant Gratification Monkey.

What does this mean for the procrastinator? Well, it means everything's fine until this happens. So, the Rational Decision-Maker will make the rational decision to do something productive, but the Monkey doesn't like that plan, so he actually takes the wheel, and he says, "Actually, let's read the entire Wikipedia page of the Nancy Kerrigan/Tonya Harding scandal, because I just remembered that that happened."

Then—we're going to go over to the fridge to see if there's anything new in there since 10 minutes ago. After that, we're going to go on a YouTube spiral that starts with videos of Richard Feynman talking about magnets and ends much, much later with us watching interviews with Justin Bieber's mom. "All of that's going to take a while, so we're not going to really have room on the schedule for any work today. Sorry!"

Now, what is going on here? The Instant Gratification Monkey does not seem like a guy you want behind the wheel. He lives entirely in the present moment. He has no memory of the past, no knowledge of the future, and he only cares about two things: easy and fun.

Now, in the animal world, that works fine. If you're a dog and you spend your whole life doing nothing other than easy and fun things, you're a huge success! And to the Monkey, humans are just another animal species. You have to keep well-slept, well-fed, and propagating into the next generation, which in tribal times might have worked OK. But, if you haven't noticed, now we're not in tribal times. We're in an advanced civilization, and the Monkey does not know what that is.

Which is why we have another guy in our brain, the Rational Decision-Maker, who gives us the ability to do things no other animal can do. We can visualize the future. We can see the big picture. We can make long-term plans. And he wants to take all of that into account. And he wants to just have us do whatever makes sense to be doing right now.

Now, sometimes it makes sense to be doing things that are easy and fun, like when you're having dinner or going to bed or enjoying well-earned leisure time. That's why there's an overlap. Sometimes they agree. But other times, it makes much more sense to be doing things that are harder and less pleasant, for the sake of the big picture. And that's when we have a conflict.

And for the procrastinator, that conflict tends to end a certain way every time, leaving him spending a lot of time in this orange zone, an easy and fun place that's entirely out of the "Makes Sense" circle. I call it the Dark Playground.

Now, the Dark Playground is a place that all of you procrastinators out there know very well. It's where leisure activities happen at times when leisure activities are not supposed to be happening. The fun you have in the Dark Playground isn't actually fun, because it's completely unearned, and the air is filled with guilt, dread, anxiety, self-hatred—all of those good procrastinator feelings.

And the question is, in this situation, with the Monkey behind the wheel, how does the procrastinator ever get himself over here to this blue zone, a less pleasant place, but where really important things happen? Well, turns out the procrastinator has a guardian angel, someone who's always looking down on him and watching over him in his darkest moments—someone called the Panic Monster.

Now, the Panic Monster is dormant most of the time, but he suddenly wakes up anytime a deadline gets too close or there's danger of public embarrassment, a career disaster, or some other scary consequence. And importantly, he's the only thing the Monkey is terrified of.

Now, he became very relevant in my life pretty recently, because the people of TED reached out to me about six months ago and invited me to do a TED Talk. Now, of course, I said yes. It's always been a dream of mine to have done a TED Talk in the past.

But in the middle of all this excitement, the Rational Decision-Maker seemed to have something else on his mind. He was saying, "Are we clear on what we just accepted? Do we get what's going to be now happening one day in the future? We need to sit down and work on this right now." And the Monkey said, "Totally agree, but let's just open Google Earth and zoom in to the bottom of India, like 200 feet above the ground, and scroll up for two and a half hours till we get to the top of the country, so we can get a better feel for India." So, that's what we did that day.

As six months turned into four and then two and then one, the people of TED decided to release the speakers. And I opened up the website, and there was my face staring right back at me. And guess who woke up? The Panic Monster starts losing his mind, and a few seconds later, the whole system's in mayhem. And the Monkey—remember, he's terrified of the Panic Monster—boom, he's up the tree! And finally, finally, the Rational Decision-Maker can take the wheel, and I can start working on the talk.

Now, the Panic Monster explains all kinds of pretty insane procrastinator behavior, like how someone like me could spend two weeks unable to start the opening sentence of a paper, and then miraculously find the unbelievable work ethic to stay up all night and write eight pages. And this entire situation, with the three characters—this is the procrastinator's system. It's not pretty, but in the end, it works.

This is what I decided to write about on the blog a couple of years ago. When I did, I was amazed by the response. Literally thousands of emails came in, from all different kinds of people from all over the world, doing all different kinds of things. These are people who were nurses, bankers, painters, engineers, and lots and lots of PhD students.

And they were all writing, saying the same thing: "I have this problem too." But what struck me was the contrast between the light tone of the post and the heaviness of these emails. These people were writing with intense frustration about what procrastination had done to their lives, about what this Monkey had done to them.

And I thought about this, and I said, well, if the procrastinator's system works, then what's going on? Why are all of these people in such a dark place? Well, it turns out that there's two kinds of procrastination. Everything I've talked about today, the examples I've given, they all have deadlines. And when there's deadlines, the effects of procrastination are contained to the short term because the Panic Monster gets involved.

But there's a second kind of procrastination that happens in situations when there is no deadline. So if you wanted a career where you're a self-starter—something in the arts, something entrepreneurial—there's no deadlines on those things at first, because nothing's happening, not until you've gone out and done the hard work to get momentum, get things going.

There's also all kinds of important things outside of your career that don't involve any deadlines, like seeing your family or exercising and taking care of your health, working on your relationship, or getting out of a relationship that isn't working. Now, if the procrastinator's only mechanism of doing these hard things is the Panic Monster, that's a problem, because in all of these non-deadline situations, the Panic Monster doesn't show up. He has nothing to wake up for, so the effects of procrastination, they're not contained; they just extend outward forever.

And it's this long-term kind of procrastination that's much less visible and much less talked about than the funnier, short-term deadline-based kind. It's usually suffered quietly and privately. And it can be the source of a huge amount of long-term unhappiness and regrets. And I thought, that's why those people are emailing, and that's why they're in such a bad place. It's not that they're cramming for some project; it's that long-term procrastination has made them feel like a spectator, at times, in their own lives. The frustration is not that they couldn't achieve their dreams; it's that they weren't even able to start chasing them.

So, I read these emails and I had a little bit of an epiphany—that I don't think non-procrastinators exist. That's right—I think all of you are procrastinators. Now, you might not all be a mess, like some of us, and some of you may have a healthy relationship with deadlines, but remember: the Monkey's sneakiest trick is when the deadlines aren't there.

Now, I want to show you one last thing. I call this a Life Calendar. That's one box for every week of a 90-year life. That's not that many boxes, especially since we've already used a bunch of those. So, I think we need to all take a long, hard look at that calendar. We need to think about what we're really procrastinating on, because everyone is procrastinating on something in life. We need to stay aware of the Instant Gratification Monkey. That's a job for all of us. And because there's not that many boxes on there, it's a job that should probably start today. Well, maybe not today, but... you know. Sometime soon.

This talk by Tim is almost exactly 9 years old. The video has 58 million views on YouTube, making it one of the most popular videos in the history of the Ted project.