So how's it going guys? Tell me, did you know that in certain situations, poker requires that we must bluff? That sometimes not bluffing would be such a gross theoretical mistake that it could be compared to pushing all-in preflop from the small blind with 97s for 100bb, or folding top pair on the flop before it was our turn to act. Yes, yes, such a serious mistake can be made simply by not daring to bluff in one of these situations. Let's stop leaving money on the table and learn how to pick it up with mandatory bluffs. I hope this video gives you a fair amount of information and you learn to notice these situations and use them.

We will study three examples and first look at a blind hole-card hand. Think about the interaction of ranges, about whose range is stronger and who benefits from certain texture changes in combination with the actions of the players. We must learn to recognize when our range is so much stronger than our opponent's range that when we get to the river with a hand that has no showdown value, we always have to bluff it.

Here are the situations we will be talking about today:

1. Narrow range against a line that gives up a lot.

2. Good runout + opportunity to play bet-check-bet.

3. Excellent blocker + the ability to bet a third barrel.

Let's go in order.

So, 6-max cash, zoom 200 on PokerStars, 100bb. The cutoff raises to 2.5bb and I defend the big blind.

Flop – . I check, Villain bets 2.62bb. I call.

Turn – . I check, and my opponent checks next.

River – . And we come to a decision about a possible bluff.

If you're not bluffing here with my hand, that's okay – work hard and learn, but until you learn, you're making a huge, gigantic mistake. Let's take a look at my cards.

This hand represents the lack of value at showdown. The inability to win at showdown is an argument for bluffing, but it's only the first step. What makes our bluff mandatory is the presence of fold equity. Where does such a large fold equity come from that a bluff becomes automatic? The fact is that on the river our range has become noticeably stronger than the opponent's range. The advantage is on our side!

How to recognize it? Let's go through the hand. Villain c-bets quite wide on the flop, maybe not with all hands, but there are a lot of bluffs anyway. His next check on the blank turn is a key fork in the hand. By giving up on the second barrel, Villain not only showed he didn't have the nuts in his range but also got to the river with a lot of trash hands. Yes, some gutshots and flush draws go for a second barrel, but completely hopeless hands will prefer to give up right away.

Of course, I'm not saying that our opponent always checks the turn to fold on a blank river, but a significant part of his range on such a line is air.

We don't have the nuts in our range either, but that doesn't matter. Overall equity depends not only on the nuts, but also on weak hands. Villain forced us to pay a continuation bet and thereby narrowed and condensed our range a lot. We dropped the weakest part of the range, unlike the Villain, who carried it to the river. Therefore, we are claiming a larger share of the pot and therefore should bluff with worse hands.

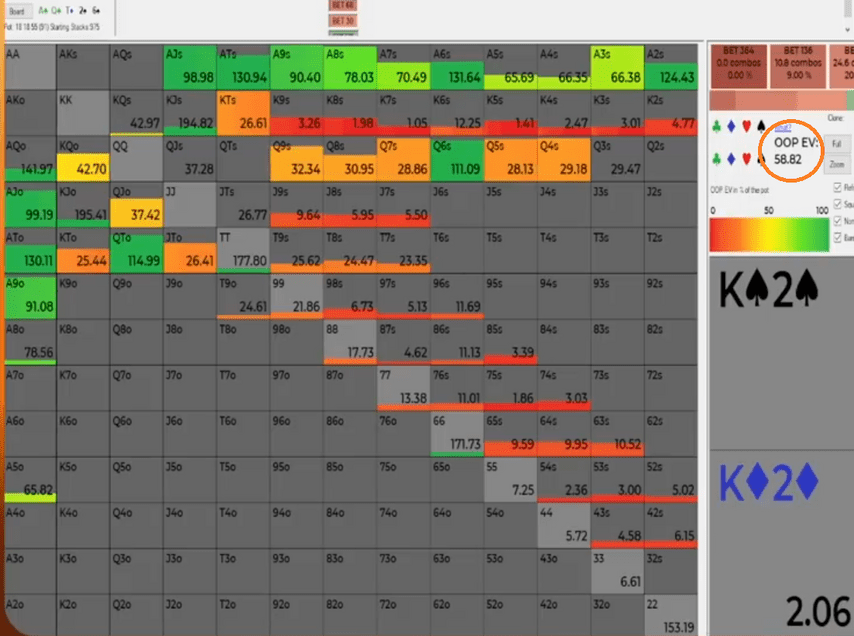

Here is our opponent's strategy on the turn as the solver sees it:

His checking range consists of underpairs that would prefer low cards, gutshots that sometimes bluff and sometimes don't, queen pairs that can call the river or give up, and weak top pairs that are major bluff catchers.

He checks and the river is an offsuit six. We can look at the solver for the total equity of our range and the river strategy.

As you can see, our equity is almost 59%; we are noticeably stronger. The main reason for this advantage is that we have almost no weak hands because we called on the flop. The only exceptions are empty flush draws.

According to the solver, almost any bet with , except for an all-in, will bring us about 3% of the pot. An all-in will be a loss, and of course, we will get 0 when we check. Therefore, the bluff is obviously profitable, and refusing it is a very bad play.

If on the flop we had , having caught a pair on the river, we can just check: this gives 11% of the pot versus 9-9.5% in case of a bluff.

When we bet 3/4 of the pot, the solver folds 47% of hands to our opponent! It overfolds a lot compared to the minimum defense frequency because the minimum defense frequency cannot be used when one range is much stronger than the other.

That, in fact, is all. I hope you understand the first situation. Caution on this line should be exercised on bad rivers for us when some of our hands with no showdown value are forced to give up or bluff with little weight. But as it is, you have an advantage, so demand what is rightfully yours!

You can't justify checking because you have bad blockers because you don't want to block a missed flush draw. This is not the case. The correct line of thought is that my hand can't win at showdown, but my range is generally stronger, so I'm allowed to bluff even with this hand.

A positive action does not mean that we will always win! You have seen that the solver calls 53% of his hands, meaning we lose more than we win. And this time I lost too: I bet 7.44bb into a 10.73bb pot and my opponent called with . Such calls should not upset us. We weren't planning on knocking an ace out, were we? It's a logical call with a logical hand that doesn't invalidate our strategy at all. The bluff was good, and all doubts about it are groundless.

Ok, next hand. The next line is the opportunity to bet-check-bet on a suitable runout. Zoom 200, 100 blinds. We raise 2.5bb from the button. BB calls.

Flop . We continue with a c-bet of 1.57bb and Villain calls. Turn – , check – check. River – . Villain checks again and we bet 6bb into an 8.64bb pot.

The profitability of our bluff is very texture dependent. I'm not saying that it's always profitable to bluff the bet-check-bet line. There are turns and rivers that only make things worse for our range. Therefore, we first need to figure out what combinations of turns and rivers are beneficial for us after our opponent calls our continuation bet.

Good cards for us improve the hands that our opponent folded on the flop. What does he fold to a c-bet? Hands without a pair, no strong ace, no straight draws, and no strong backdoors. , for example. Often kings will fold – , , , 10-high, etc. So a king, jack, ten on the turn or river is pretty good for us.

What cards are good for the opponent? Sixes, fives, fours, threes, whatever goes well with hands that hit the flop enough to call.

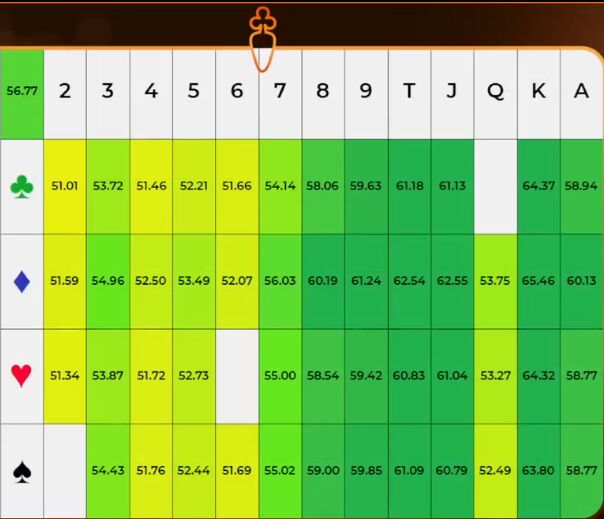

In the solver, you can look at more and less profitable runouts for us.

So the jack on the turn is our card, one of the best, if not as good as a king. We, however, refused the second barrel. Maybe right, I don't know – it depends on our cards. But it's such a good runout for our range that we might as well put some of our bluffs on one street – few river cards will change that.

The fraction of the pot our range holds after our opponent checks on the river is almost 61%.

Let's see what the solver does on the river.

We often bet with sets, overpairs, good top pairs, and bluffs. We always bluff with , , winning 5-7% of the pot – a huge profit in the long run!

In general, betting-checking-betting on a texture that is favorable for us is a great line for aggressive bluffs.

(Peter had , he did not show the hand that the opponent called with.)

The last topic for today is three barrels with excellent blockers. We are looking for situations where our blockers are so good that they leave us no choice.

First, a few words about three barrels. When you use a bet-bet-bet (or overbet) line on this or a similar texture:

It's important to remember that checking on the river doesn't weaken Villain's range because it has no alternative. Our range on this line is very polarized, we have a lot of nuts and a lot of air. But don't confuse the advantage of the nuts with the advantage of the range equity, it's not the same thing and doesn't always match up, just as it doesn't now. We have, for example, or , and Villain's hands of this type folded on the turn.

So this is not a situation where we have the right to get all hands without value to showdown. To select hands for bluffs, you need to look at blockers. And some blockers are so good that it's a real crime not to bluff with them.

Stop and think about what hands you need to bluff with here. A couple of hints: they unblock the opponent's automatic folds and block his calls.

Obviously, it's bad for us to have diamonds. Villain calls two-barrels with high flush draws and folds the river. Blocking high flush draws should be taboo for us.

And from what do we get called most often? , , . Blocking these kickers would be very useful for us.

Having said all this, we come to the conclusion that the bluff with my hand – – is inevitable. Even when I c-bet the flop, I said to myself: “Wow, what blockers! Looks like three barrels." It's a mandatory bluff in this thread.

As in the other examples, Villain called and showed . I deliberately selected hands with correct bluffs that didn't work. In the life of a professional grinder, in the face of strong opponents (and the 200 zoom is pretty high), you have to be prepared to lose hands while bluffing. It's not shameful. This shouldn't upset us.

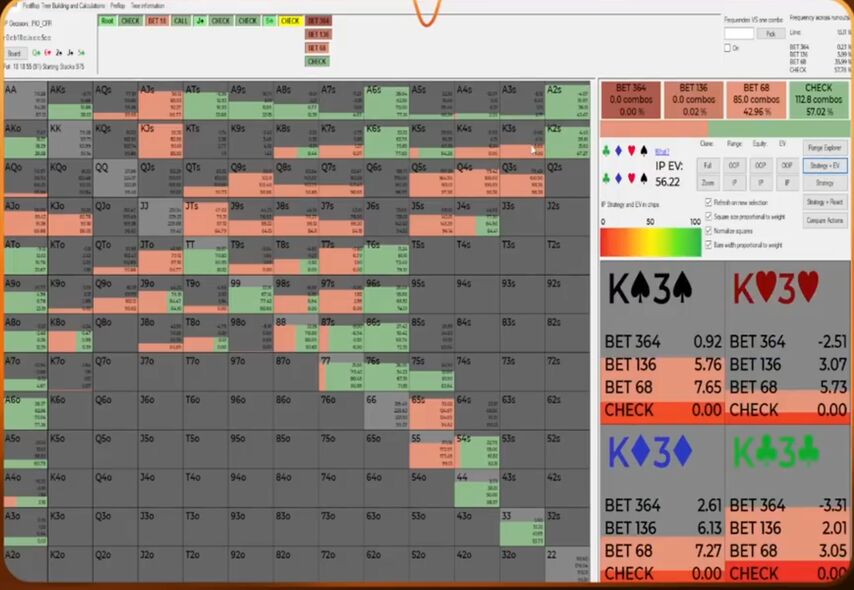

Let's see what the solver does on the turn.

He doesn't overbet because we don't need an overbet to make a significant proportion of Villain's hands indifferent to calling. 75% is fine. they mix bets and checks, but they bet more often without diamonds. There are no pure, 100% bluffs with any hands at all, everyone prefers to use a mixed strategy.

And here is the river.

And that's all bluffing without a jack of diamonds. According to the solver, the relevant flush blocker is only a jack, it does not pay much attention to the nine. An overbet bluff gives us 1% of a decently overinflated pot, while a check does nothing.

What are we giving up on? Blockers are worse. For example, a bluff with will be decently negative, -1.76% of the pot (the EV of the check is zero next). Most often, the solver calls with and , so a ten is a good blocker, but diamonds make the bluff unprofitable.

I wouldn't call refusing to bluff an outright monstrous mistake, but it's rather weak and can become a problem. In fact, it is quite difficult to accurately assess whether a real opponent will overfold or underfold, so it is quite risky to deviate sharply from GTO. It is important not to overdo it with generalizations. "He won't fold, I check" is just as bad as "I can't win at showdown, so I have to overbet." It's better to stick to the system. And the system tells us that in a three-barrel situation with good blockers, we should bluff.