You're currently making lots of mistakes at the tables that are costing real money, and yet you have no clue about them.

Let's get into it. We're going to use a specific post-flop leak to demonstrate how you've been getting exploited all this time by your opponent.

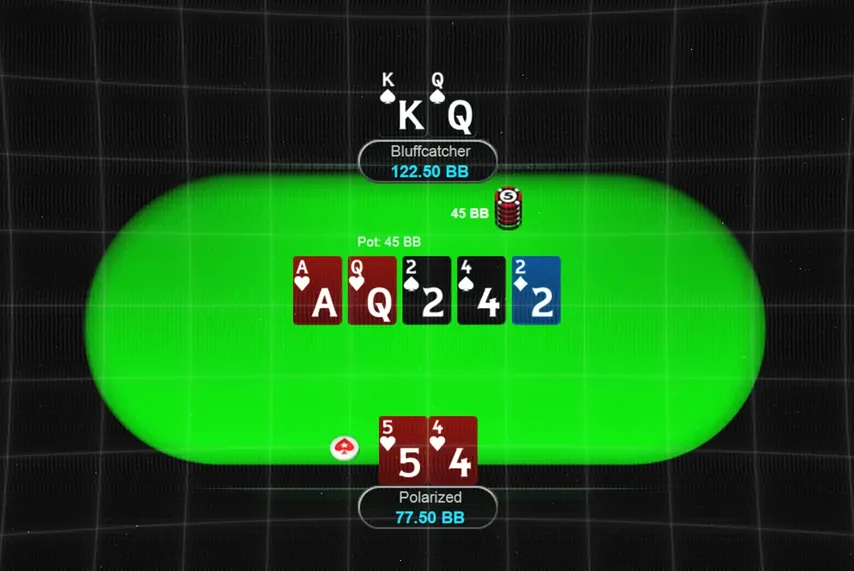

At first glance, this hand looks really standard. The hero opens pre-flop with the and gets called by the big blind. On a semi-connected flop, the hero decides to check behind with a hand that has low equity and poor blockers. Then, on the turn, facing a small bet with an unimproved hand, the hero decides to fold, which is the correct decision in GTO terms.

So What is the Problem Here?

The thing is that defending against turn probes is one of the most difficult things you can do in poker. When we study the behavior of the best players in the world—the ones actually taking home millions from the poker tables every year—we see that even they fold too much when facing these bets. While a GTO bot would only fold about 22% of the time against a small all-in turn probe, regular players fold 29%, which is a 7% over-fold relative to a balanced strategy.

When we take a look at mere mortals at 15NL, the leak is significantly higher—a crazy 14% over-fold relative to solver.

Now, before we talk about what are the reasons that cause this over-folding, you should actually be asking yourself: Is over-folding here really a problem? We established that 99.9% of humans fold more than they should in this situation, but is that really costing you money? This is a fair question because not all deviations from solver are a mistake in practice.

For example, a lot of people argue that you should over-fold against recreational players on the river because they don't bluff much. Well, over-folding is a deviation from solver; it's exploitable to over-fold if the assumption that your opponent doesn't bluff much is true.

It's a negative EV investment to call river bets against someone who's under-bluffing; therefore, deviating from solver against them is not a mistake but rather the proper maximum EV play.

So how can we know whether over-folding against turn probes is a leak that costs us money or a good exploit that increases EV? To answer that question, we need to study the behavior of our opponents. We need to figure out whether their betting range construction incentivizes an over-fold or an overall fold, and that's where things might start to get tricky.

Hold On – It's Not That Simple

Do you even know what their strategy needs to look like for you to want to over-fold on the turn? Things aren't so simple on the turn like they are on the river. On the river, all you need to know to decide whether to call or fold against a bet is how many bluffs your opponent has with his particular bet sizing. If they bet half pot, they need to be bluffing 25% of the time for you to break even. If they bluff more than that, then your bluff catcher is positive EV and you should always call. If they bluff less than that, then your bluff catcher is negative EV and you should always fold.

For the turn, however, simply knowing how many bluffs they have on the turn is not sufficient to decide whether you want to call or fold a marginal bluff catcher. Take a look at this toy game—the classic polarized versus bluff catcher toy game—but in this case over two streets. Action starts on the turn with the polarized range being able to either bet pot or check on the river. The polarized range has the same options: either a pot bet or a check.

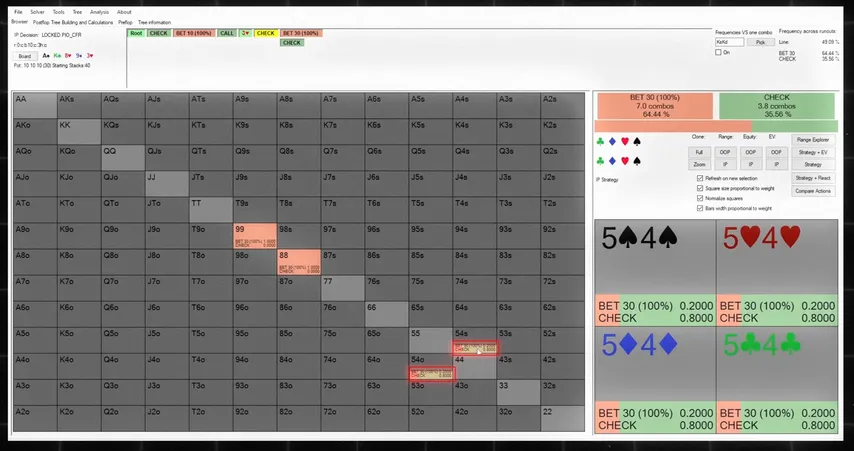

When the polarized range has six value combos, the optimal solution to this game is for the IP player to bet on the turn with a total of 13 combos—six combos of value and seven combos of bluffs. This constitutes a 1.25 bluff-to-value ratio. What happens if I force the IP player to under-bluff on the turn, reducing their betting frequency of bluff combos from 46% to let's say 30%? Surely the OP player now will start folding everything right just like on the river? Well, not necessarily.

It's possible for you to want to over-fold on the turn even if your opponent is under-bluffing on the turn like the simulation shows. For you to understand this, you need to understand how we make money calling turn bets with bluff catchers. Why? On the river, we break even with our call by winning at showdown at exactly the same percentage as our pot odds we were given on the turn.

The way we make money calling a bet is by not facing a bet on the next street. The reason for this is that, in theory, our opponent should make us indifferent to calling or folding against his river bet. In other words, it makes no difference for us to fold or to call when we face a river bet. We could just always fold the river, and our expected value would be the same against a fixed strategy. Therefore, facing a river bet after calling a turn bet loses us money. Every time we face a river bet after calling a turn bet, we simply lose the amount we called on the turn.

From that, it follows that the only way to break even with a turn call is by compensating for the money we lose by facing a bet with the money we win when not facing a bet. In other words, we need to get to showdown and win against our opponent's hands. In the GTO solution for the previous toy game, we face a pot bet on the turn. This means that we're getting 33% pot odds on a call; we need to win this hand 33% of the time to break even. Since we're supposed to be made indifferent on the river by our opponent's betting range construction, it follows that for us to break even with this turn call, we need our opponent to give up 33% of the time on the river.

If we can get to showdown by facing a river check a third of the time, then the money we lose by calling the turn to face a river bet will be properly compensated by the money we win by getting to showdown. That's exactly what happens in the solver: the IP checks the river 33% of the time. What matters most to you when calling a turn bet is how often your opponent gives up on the river. That's why it's possible to over-fold on the turn even against someone who under-bluffs.

If your opponent under-bluffs on the turn by betting fewer bluff combos than he should but continues to under-bluff on the river by checking too much with his air, you can still get to showdown more often than you need to break even on your turn call, allowing you to make money with your bluff catcher even against an under-bluffing opponent. That's what I simulated in that solution I showed you before: IP is under-bluffing on the turn, but I also forced him to under-bluff on the river. This way, OP can profitably call the turn by getting to showdown more often than he needs to break even.

If you want to figure out whether you should over-call or over-fold against a turn probe from your opponent, you need to take a look at how often they give up on the river after betting the turn. If they give up more than 33% of the time, then you should likely over-call on the turn.

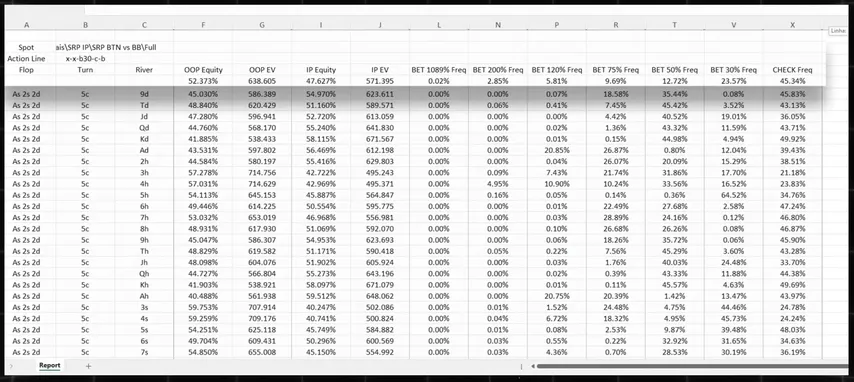

Let's take a look at the numbers for real players in the big blind versus button spot. You can determine how often solver gives up on the river after betting the turn by running an AG Gator report. This is a feature of most solvers where the program goes through all the hands you have solved and extracts information you want to analyze, like equity, EV, and of course, strategy frequencies. With all that data, the program also calculates average frequencies across all runouts, which is exactly what we want for this particular line.

Solver checks the river 45% of the time with solver frequency at hand. We can go after player pool frequency by running range research on Hand2Note, one of the most powerful poker trackers in the market. Hand2Note is so complete that not only do you get usual features from a tracker like HUDs and stats, but you can also use it to study population tendencies and maximize your EV.

In my range research report, we can see that regulars bet the river 56% of the time after betting small on the turn. The checking frequency is one minus the betting frequency; therefore, they're giving up on average 44% of the time. While they're giving up less than solver by 1%, what this means is that by calling their turn bet, you get less often to showdown than against a balanced player.

So I guess we should over-fold, right? The money we lose by calling turns to face a river bet is not being compensated by getting to showdown? Well, no—at least not in this case. A few moments ago, I told you how what matters most when calling a turn bet is how often your opponent gives up on the river.

What I didn't tell you is that there are other things that also matter.

One of these factors is that depending on your opponent's strategy, you can actually make money on the river by facing a bet. Recall how we said that we lose our investment from calling on the turn every time we face a bet on the river? This happens because our opponent was a balanced player who would always make us indifferent.

with his river bet in this circumstance, there's no money in facing a river bet. You always have a zero EV call, and therefore it works as if you just folded every time.

Your opponents, however, are not balanced players; they won't make you indifferent on the river with their betting range construction. In fact, quite the opposite: their river betting range generates you a lot of EV.

If you're new here on my channel, what I'm about to tell you might be a bit surprising, while those who have been here for some time already know this. The thing is that most players over-bluff rivers in most lines. You can make quite a lot of money with bluff catchers when facing bets from them simply because you will win at showdown way more often than you should to be indifferent.

In this specific line, for example, when regulars bet small on the turn and then bet three-quarters pot on the river, they have 45% bluffs, with 4% of those being low pairs. If we discount these low pairs, this means that any pair hand you have will win at showdown around 41% of the time. A three-quarters pot bet on the river needs 30% bluffs to be balanced; therefore, the regular players are over-bluffing by at least 11%. Calling such a bet on this line with a pair, considering that the pot will be around 8.8 big blinds on the river, will net you more than two big blinds for every call.

Let that sink in for a moment: every time you face a river bet from a regular on this line with a pair, you'll be making more than two big blinds per hand. So contrary to what happens against a balanced player, we actually make substantial money by facing a river bet since we're getting to showdown almost as frequently as against a balanced player. When facing a bet, we actually make a lot of money instead of nothing.

It follows that we should massively over-call the turn with our bluff catchers. And there's more: the title of this video is that you're getting exploited without knowing—not that you're leaving some money at the table by not exploiting a pool of balanced players. For a behavior to be a leak that is getting exploited, we need one more element that hasn't been mentioned.

This element truly causes an EV loss. To understand this element, you need to grasp what constitutes a frequency mistake and what constitutes an EV loss mistake. An EV loss mistake occurs when you pick a strategic option that is not the highest EV option at equilibrium. For example, you make an EV loss mistake when you choose to bet small with a hand that always wants to bet big. The difference between the EV of the option you took and the EV of the action you should have taken constitutes the size of your mistake; this is money you should have won but didn’t.

Since poker is a zero-sum game, what this means is that your opponent is immediately making more money from your lack of ability.

A frequency mistake, on the other hand, is when you play mixed strategy hands at wrong frequencies compared to equilibrium. In the example of our King-six hand from the beginning, you could be making a frequency mistake by choosing to check this hand on the flop 100% of the time instead of the optimal 53.8%.

You didn't play a lower EV option in this case because checking has the same EV as betting; that's the definition of a mixed strategy—two or more options make the same money. Because of that fact, frequency mistakes don't immediately cause you to lose money. If you make frequency mistakes against a fixed, balanced strategy, your EV remains the same. For you to lose money due to a frequency mistake, your opponent needs to adjust his strategy to capitalize on your leak.

In the case we're discussing, you're over-folding to turn probes mostly because you're playing mixed strategy hands incorrectly. One reason why this massive turnover in turn probes exists is that almost everyone constructs their flop check range incorrectly due to simplified heuristics, a bit of risk aversion, and a lack of proper randomizing.

Most poker players end up checking less with their complete air combos than they actually should. Truth be told here: when was the last time you over-bet with 10-9 suited or with 9-8 offsuit on an Ace-King-7 flop? Yeah, exactly—you and I both know the answer to that question.

Almost everyone in real games checks more than they should with their complete air on the flop, leaving their checking range excessively weak, which contributes to their over-fold tendency.

But not only are they checking more often with mixed strategy air combos; they're likely also not checking enough with mixed strategy strong hands and are likely also not calling enough with mixed strategy bluff catchers on the turn. These many frequency mistakes compound in your strategy and generate substantial over-fold frequency as we just stated.

However, this is not considered a leak until your opponent decides to adjust his own strategy to exploit it. How do we exploit someone who is over-folding? That's pretty simple: we start betting more with our bluff hands and our mediocre bluff catchers now make us a lot of money betting.

Therefore, the proper exploit is to start probing more with weak and marginal hands. This involves increasing the turn probe frequency by adding more bluffs and weak pairs to the betting range. If you've watched this far, you know what I'm about to say: that's exactly what your opponents are doing. When we compare the population probing strategy to solver, we see that regulars substantially over-probe with a 42% overall probe frequency. That's an 11% over-probe frequency when compared to solver performance. In relative terms, regulars probe 35% more often than solver.

When we take a look at the range composition of the small probe, we see it contains, on average, 52% bluffs and weak pairs. That's 4% to 6% more than what solver does.

The verdict here is quite clear: their over-folding tendency is getting exploited by the population. Before I ask, with this I don't mean that people are consciously doing this; some certainly are, but most people are not over-bluffing because they're consciously making a decision to attack an over-folded line. It's just a natural consequence of how they construct their ranges.

Just like you are not actually trying to over-fold, what we saw in this video highlights that you have a huge issue of over-folding to probes. This issue comes from the many frequency mistakes you make in that spot. One of your frequency mistakes is to check back less often with air hands. This makes your checking range excessively weighted towards strong hands, contributing to your over-folding with those strong hands.

Solver slow plays the flop a little bit with strong hands, and you're likely not doing that, which further increases your turn over-fold. Lastly, the third tendency that contributes to your over-folding is your lack of awareness of thresholds facing more turn probes. It's not uncommon for the GTO solution to include making calls with hands as weak as fifth pairs and even King highs. This mistake is significant because your opponents are naturally exploiting it by playing a higher-than-solver probe frequency with an over-bluffed range composition.

To make matters worse, you have a huge incentive to over-call in this scenario, as your opponents will be over-bluffing on the river, which adds a lot of EV to the turn call with your bluff catchers. I wish I had a magic formula to teach you so that you could stop this bleeding instantly, but unfortunately, I don't. Getting better at poker is about sitting in your chair every day and putting time and energy into improving. It's about studying until your brain hurts and repeating that every day for months and years straight.

Sometimes it might feel like your efforts are not being rewarded; I know I've been there. I struggled for a long time at low stakes, but I never gave up. I worked hard and eventually achieved my dream of making a living from poker. With enough effort, I'm sure you can do it too.