Does calling Ace-high for $15,000 on the river look crazy?

Well, the solver does think so, but then again, not really. This would be a call sometimes 4% of the time. But what does that mean for you in practice? Are you supposed to know this for every hand you play and then just randomize?

Well, today we're going to look at something that you can actually apply when faced with uncomfortable bets.

Linus Loeliger vs Markkos Ladev

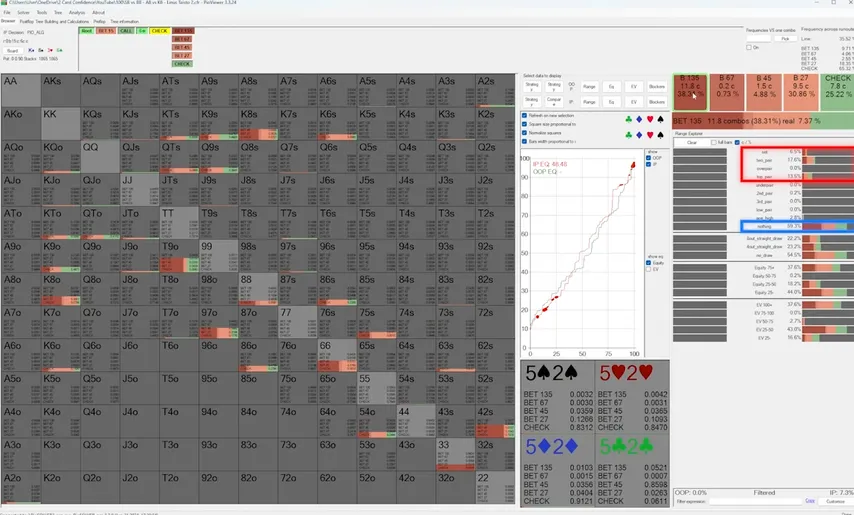

Small blind versus big blind single-raised pots are some of the most difficult ones to play. That's because ranges are really wide. On a super dry flop like King-8-3 rainbow, that means that the advantage that the small blind's open raising range had before the flop is still there. Since the big blind would 3-bet most of his best hands, his calling range is much weaker than the small blind's opening range, which includes all of these.

So with a consistent advantage across his entire range, a small bet with almost his complete range is the best play for Markkos.

And that bet gives Linus at least some difficult decisions because against it, he would not only have to find 12% of raises with pairs, he would also have to find calls with hands like suited, off, or off just to not over-fold and let Markkos make an instant profit on a small bet.

He does call and we see a on the turn.

Here, the solver splits the betting range into an overbet with top-of-the-range hands like top pair and better, and Ace-high and worse, and a small bet with pretty much a mix of everything. Since we saw that Linus's range would still include some very weak calls on the flop, a small bet could still clean up quite some equity by folding out complete airballs, but it would also allow Markkos to get another round of value with this , which could get called by a lot of weaker , , , and even and high hands that the solver would still call here.

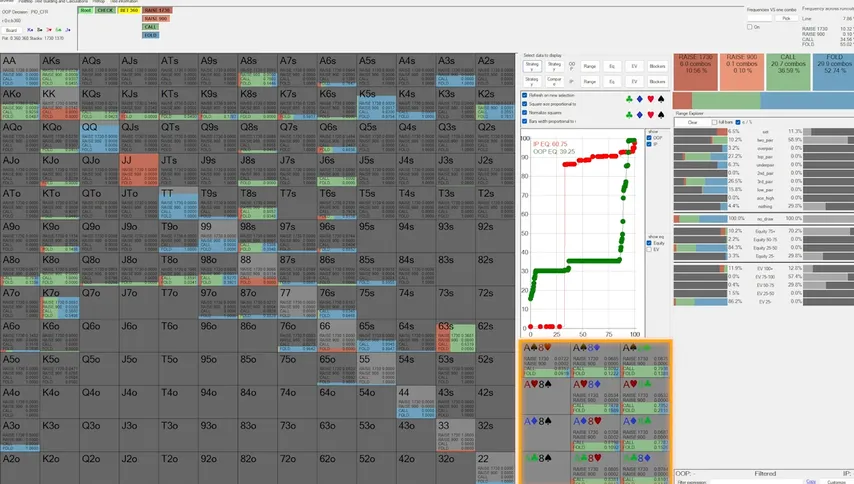

But he does decide to check, which is also a fine option, and now Linus goes ahead and bets 150% pot.

A polarizing bet like this would only happen with strong pairs and better. For the solver, that would be and better, two pair and sets, and complete air. So anything worse than -high. For those, we see that the solver prefers hands with nut equity, so straight draws, but also some -high hands are in there, presumably because they block some KingX hands in Markkos' range and can also serve as bluffs on rivers that complete a lot of the straight draws.

And for Markkos, that means that is a clear call. A pair is of course ahead of all of the bluffs in Linus's range, but it also blocks value hands like sets and two pair, which is a big factor when the value range is so narrow like in an overbet spot. But not every pair, not even every is a call. What makes the difference here is the . An makes this hand a better hand to call with because it unblocks bluffs.

Since the big blind would almost never bluff an here, having an ourselves means our opponent can have more bluffs in his range.

And the same logic applies on the river facing another bet, pot size this time.

The solver says is good enough to call here most of the time, but that just scratches the surface. As we can see, the optimal strategy for A-8 here is mixing raises, calls, and folds, which means the hand is indifferent and every one of these actions has an EV of zero big blinds. And that means that any little deviation from the equilibrium strategy that the solver calculated for our opponent can instantly change whether A-8 becomes a highly profitable call or a highly unprofitable one.

So let's have a look into what's behind the solver output, which is merely a door to a dark and unexplored world.

A Journey Into Solver Land

So as you'll know, solver results in general are way too complex for any human to actually apply in-game. So instead of looking at this simulation, taking away that Ace-8 is a call and not having a clue what to do when a different situation occurs, we'll look at two principles that you can apply to any situation like this one.

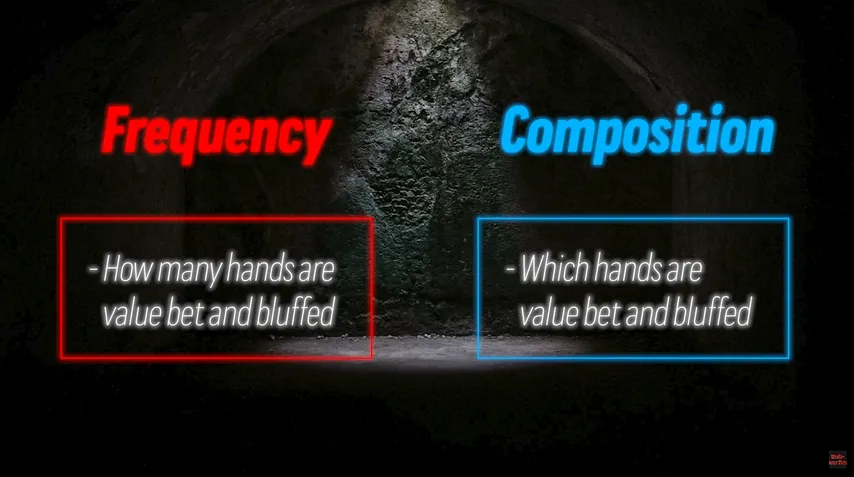

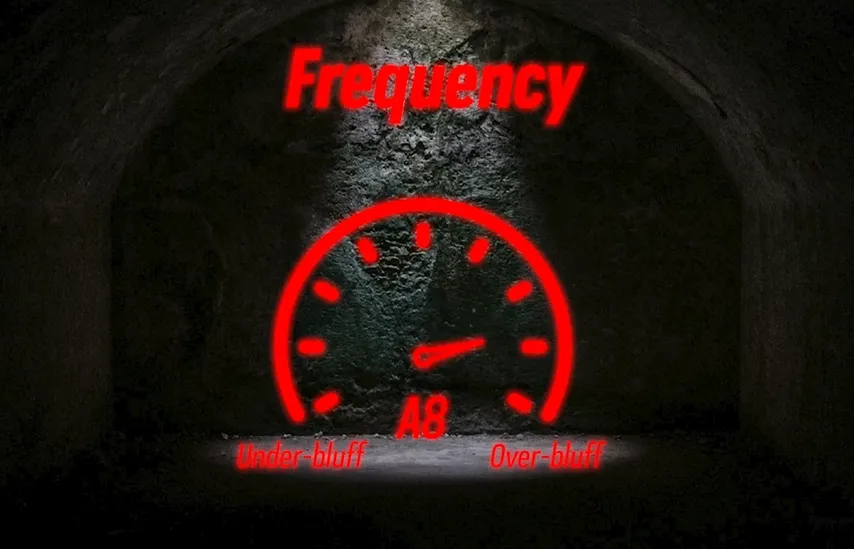

For that, we'll look deeper into our opponent's frequencies, so how many hands are value bet and bluffed, and their range composition, so which hands are value bet and bluffed.

The most important thing to look at is always the frequencies we're up against.

- How often is your opponent bluffing?

- How much is he value betting?

If you know these frequencies are off, everything else often doesn't even matter. You don't need to think about blockers if your opponent is highly over-bluffing because every bluff catcher already becomes a profitable call regardless of blockers.

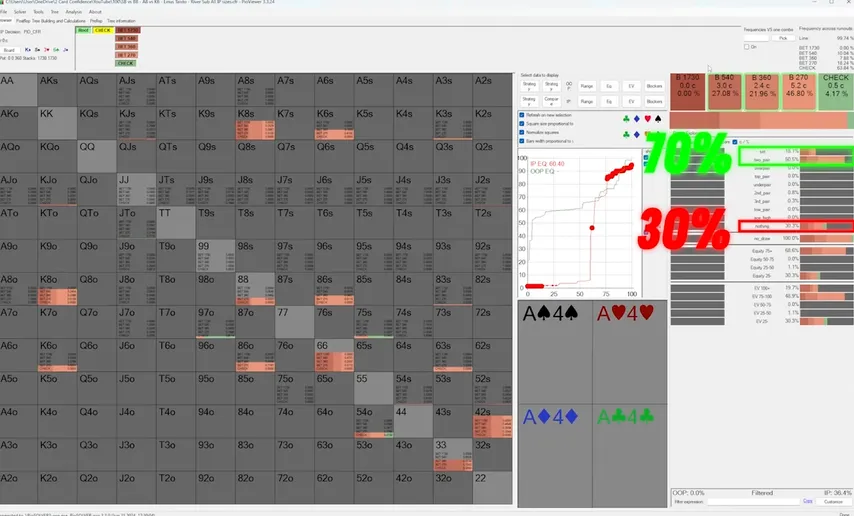

But of course, most of the time you don't know if they're over-bluffing or not, so you have to estimate it. And for that, you want to take the baseline of what the optimal strategy for the big blind would be and how much room there is for him to deviate. Here, the big blind would be betting around 36% of the time in theory. 70% of those would be value bets and 30% would be bluffs.

But when we look at the bluffs, we see that the hands the solver would choose to bet are only a fraction of those hands that could potentially bluff here. Just looking at -high and worse hands that got to the river, we see that only 20% of those would actually bet. Those would be the lowest ones, so suited and , which would never win at showdown.

But if you bluff anything else on top of that, you would already be over-bluffing.

The likelihood of the sensor swinging towards over-bluffing is higher than a tendency to under-bluff.

But even if we didn't know that or assumed our opponent would get their frequencies about right, there is something else we want to look at when bluff-catching.

As mentioned before, here blocks a lot of value hands, two pair and sets, and doesn't block any bluffs because Linus shouldn't ever bluff Ax, and both of these assumptions are very applicable in reality.

In a minute we'll look at an example where that is not the case, but here it's very reasonable to assume that not only end bosses like Linus, but most decent players on lower stakes as well will rarely, if at all, bluff , but take their bluffs from weaker hands.

Which means, is very insensitive to the big blind's range composition in this spot and will always make a good bluff catcher in that regard, both of which shift this zero EV bluff catcher to more likely being a plus EV call.

But of course, bluff catching isn't the only thing you want to master as a player.