In the 1939 story "Life Line," by Robert Heinlein, Professor Pinero invents a machine that accurately determines a person's lifespan by indicating their birth and death dates. The Academy of Sciences dismisses him, so Pinero starts his own business predicting death dates.

Modern science hasn't reached this level of science fiction yet. However, an indicator exists that predicts remaining life expectancy better than anything else, even smoking. Athletes in cyclic sports like running, skiing, and cycling know it well: VO₂ max, or maximum oxygen consumption.

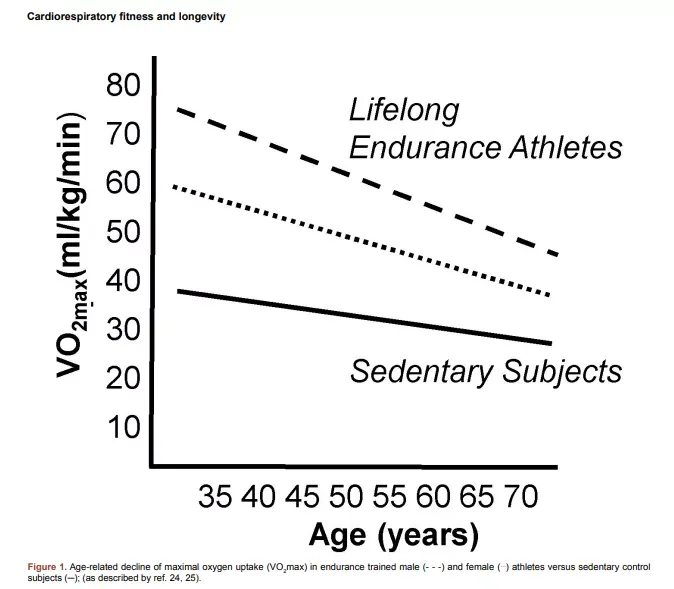

Known for over a century, VO₂ max only recently gained the attention of aging experts in the last 10-15 years. It shows the maximum amount of oxygen the body can process per minute, linking lung capacity, cell efficiency in oxygen binding and transport, capillary network branching, and mitochondrial efficiency in energy processes. Largely genetically determined but somewhat trainable, VO₂ max steadily decreases with age by about 1% per year.

The creator of this indicator, Archibald Hill, received the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

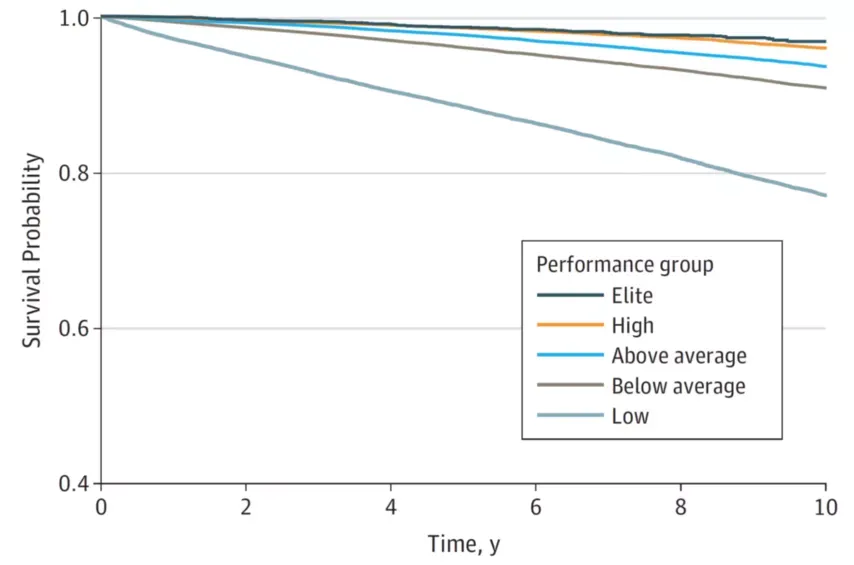

A study by Mandsager et al. (2018) of 122,000 patients with an average age of 53 divided them into five VO₂ max groups: bottom 25%, 25-50%, 50-75%, 75-95%, and top 5%. The probability of surviving the next 10 years was then assessed.

The low VO₂ max group had disastrous results, but oxygen uptake efficiency significantly affected life expectancy in other cohorts. Moving from the bottom to the middle cohort increased survival chances more than recovering from type 2 diabetes.

This makes intuitive sense. Breathing becomes increasingly difficult with age until it stops, resulting in death.

Consider climbing stairs, which requires about 16 ml of oxygen per minute per kilogram of body weight. For the average person over 70, this takes 60-80% of their aerobic endurance. Further VO₂ max declines eventually make unassisted stair climbing impossible. However, a 70-year-old in the top cohort only uses 45% of their aerobic endurance, a comfortable effort level.

There's good and bad news.

The good news: regression can be slowed and sometimes reversed in those with advanced physical condition but good potential.

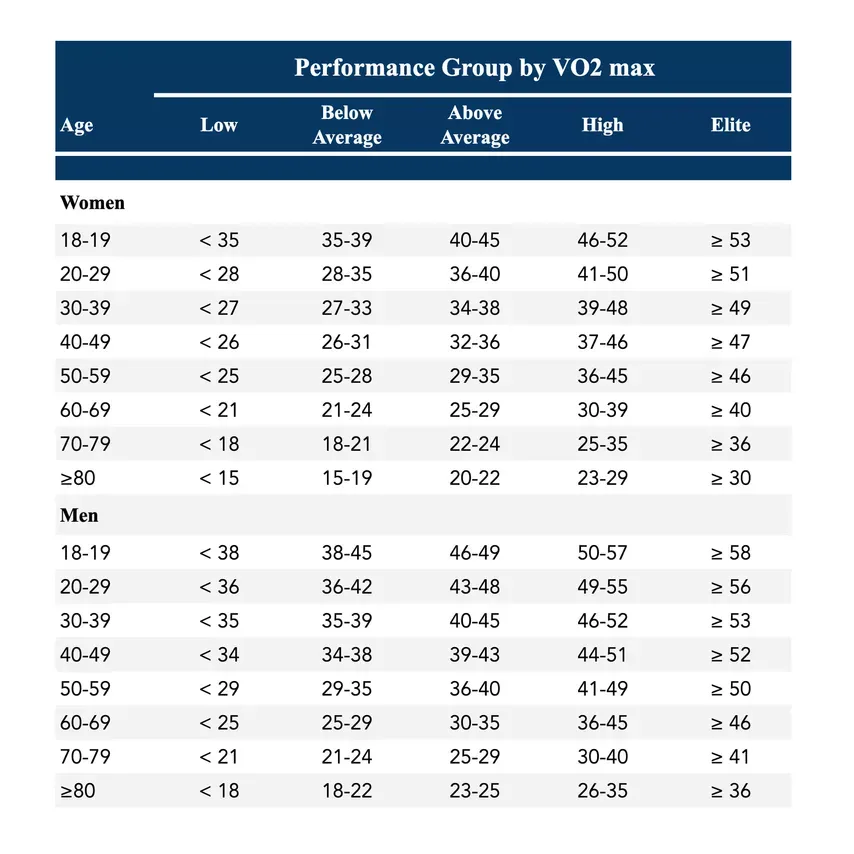

The bad news for the ambitious: most average people can never physiologically reach elite athlete levels, no matter how hard they train. For men aged 20-29, a high VO₂ max is 52-57 ml/min/kg, while a low is 32-38.

Elite athletes surpass the top cohort far more than the top surpasses the bottom:

- Oscar Svendsen (cycling) – 97.5

- Bjorn Deli (cross-country skiing) – 96.0

- Greg LeMond (cycling) – 92.5

- Gunde Swan (cross-country skiing) – 91.0

- Harri Kirvesniemi (cross-country skiing) – 91.0

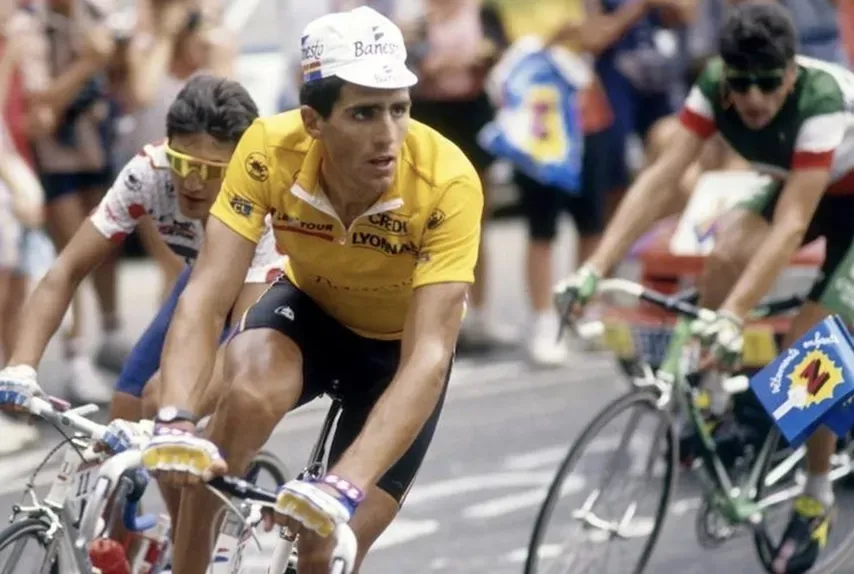

- Miguel Indurain (cycling) – 88.0

- Edward Boasson Hagen (cycling) – 86.4

- Ole Einar Bjoerndalen (biathlon) – 86.0

- Chris Froome (cycling) – 84.6

- Lance Armstrong (cycling) – 84.0

The record holder only won the Junior World Championship and skated professionally for two years. Sports fans likely know the rest.

But if your goal is a longer, happier life rather than world domination or Olympic medals, the good news applies. According to former pro cyclist and Global Cycling Network host Dan Lloyd, a 70-year-old in the top VO₂ max cohort absorbs oxygen as efficiently as the average 30-year-old, which is achievable for most with proper training.

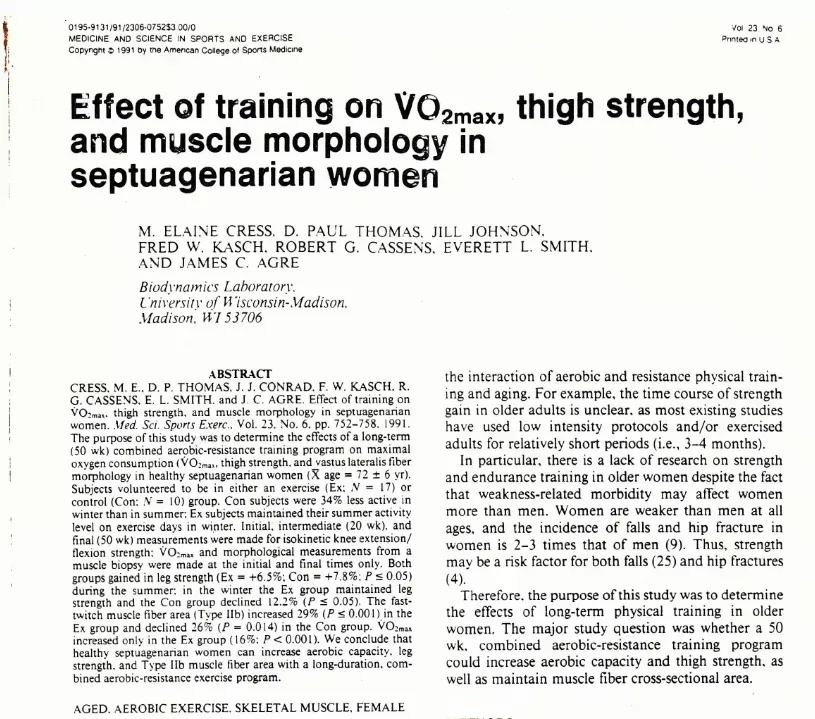

Studies show that relatively simple training can improve VO₂ max in older women by 12.6% over 12 weeks (Warren et al., 1993) and 16% over 50 weeks (Cress et al., 1991).

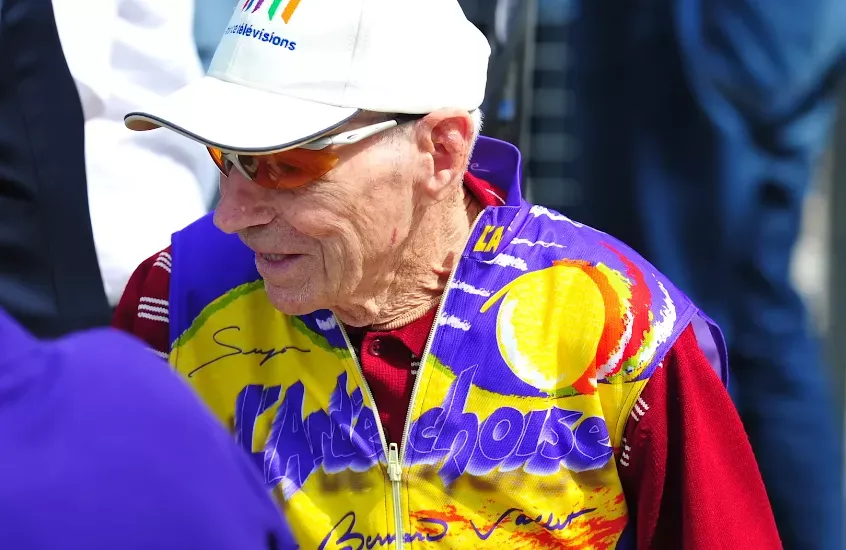

Another inspiring example is Frenchman Robert Marchon, who lived to 109, trained an hour daily on a bicycle until 108, and set one-hour cycling records for ages 100-104 and 105+. He increased his VO₂ max from 31 to 35 between setting Guinness records at 101 and 103, a 13% improvement that rivaled those 40 years younger. Only deafness stopped his riding.

Science concludes that if you're healthy enough to exercise, you're guaranteed to be in the top 25% of your age cohort.

VO₂ max can be measured in a lab on a bicycle ergometer under medical supervision. It costs $100-150 in developed countries and is available at many medical centers. Annual monitoring suffices. Many smartwatches estimate VO₂ max for free, albeit with low accuracy, which is still better than nothing.

Since VO₂ max is measured by oxygen absorption per kilogram, increasing it requires improving cardiovascular efficiency or losing excess weight. The latter seems simpler, but losing muscle mass is extremely undesirable, so recomposition is necessary, which is also challenging. Working on both simultaneously is advisable.

The elderly women in the cited studies did an hour of walking five days a week and climbed stairs with weights. More ambitious readers may prefer more intense methods.

Consult a doctor before starting VO₂ max workouts, as they significantly stress the cardiovascular system. Here's one:

After a 15-30 minute gradual warm-up, do four 4-minute intervals at your maximum sustainable effort, with 4-minute recoveries in between.

Just 16 minutes, but it's more than enough. Dan Lloyd recommends starting with three intervals and only moving to four after a few workouts. Eventually, increase to six intervals. Do this training no more than once a week and only when well-rested.

Another GCN video recommends six 30-second sprints with two-and-a-half-minute breaks for VO₂ max training. Distributing effort over 30 seconds may be easier than 4 minutes, but it won't be pleasant either way.

More foreign recommendations and warnings for the prepared:

– Don't start VO₂ max training until completing 6-8 anaerobic threshold sessions.

– The truly unpleasant workouts enter the oxygen debt zone but yield the greatest effect. Be patient! A good warm-up is critical for these workouts.

– Warm up thoroughly – this is critical!

– Do 6 short, 3-minute bursts as fast as possible, ideally on an even uphill slope. Find a smooth, sustainable 3-minute speed and repeat 6 times with 3-minute rests. It will hurt, darken your vision, and possibly make you taste blood, but it's worth it.

– Ride 10 minutes, then do four 2-minute segments at slightly higher intensity. Don't trust the heart rate monitor.You'll remember this hour and a half for a long time! Never do this workout without recovering from something hard.

But you can start small. The main thing is to keep moving, as understood even in Lewis Carroll's time.