In both poker and chess, if you haven't caught a cheater red-handed, you have to rely only on circumstantial evidence. The scandal over the possible cheating of the young American chess player Hans Niemann, which began after Niemann defeated the world champion Magnus Carlsen playing as black, has developed powerfully in recent days: with a difference of several hours, an article in the Wall Street Journal and a 72-page report by the anti-cheating team of the chess website were published .com. However, it seems to us that the most convincing circumstantial evidence of Niemann's guilt was demonstrated in a short YouTube video by the Brazilian chess enthusiast and programmer Rafael Leite.

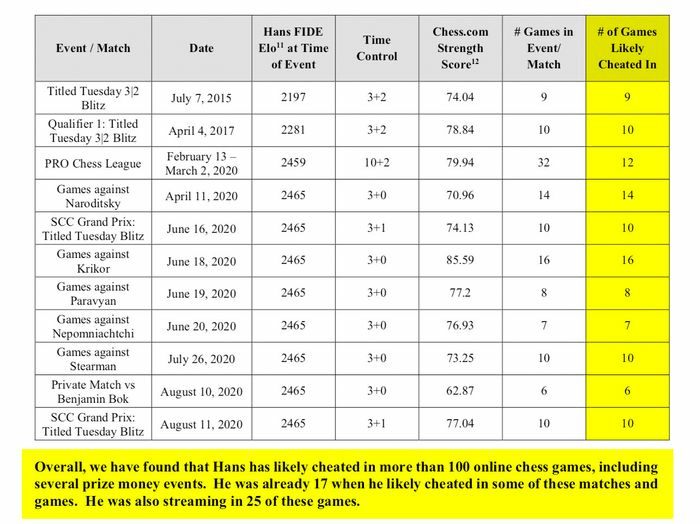

Last month, world chess champion Magnus Carlsen suggested fraud by American grandmaster Hans Moke Niemann. Niemann, 19, replied that he only used computer prompts during games, when he was 12 and 16 years old. However, an investigation by Chess.com, the gaming platform where many of the world's top players play, showed that he cheated much more often.

The report, which came into the hands of the authors of the WSJ, states that Niemann with a high probability received computer help in more than a hundred games played on the Internet, the latest of which date back to 2020. Some of these games were played in tournaments with prizes. Chess.com uses several methods to detect cheaters, including comparing the player's moves against recommendations from various computer programs, each of which can beat the strongest human player on demand.

The report also states that Niemann admitted to the allegations and was banned from the site for a while.

The authors of the report also draw attention to the unusual speed of Niemann's rise to the elite level in live chess. However, while Chess.com calls it a "statistically extraordinary event," the report emphasizes that Chess.com has no experience in identifying cheaters in classical chess. The authors call for additional investigation into some of the most suspicious tournaments involving Niemann. The International Chess Federation is currently conducting its own investigation into the incident that occurred in the games of Niemann and Carlsen.

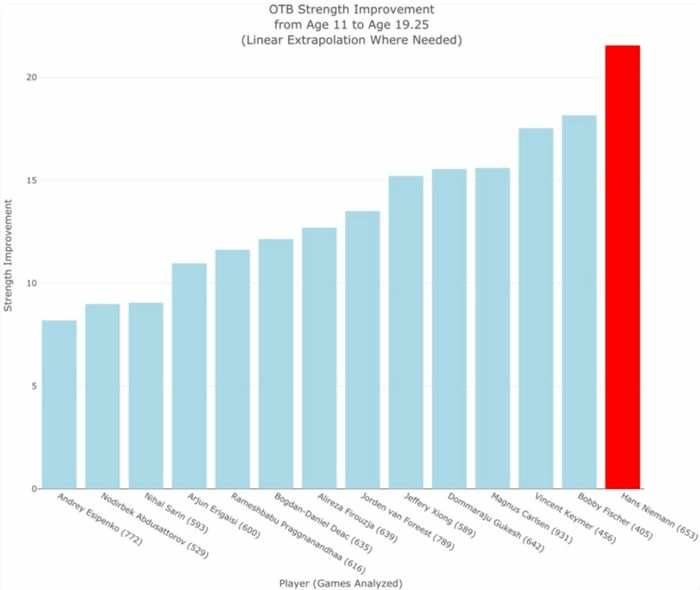

"Niemann's rise in live play in classical chess was the fastest in recent chess history," writes Chess.com and compares him to other brilliant young players of today, as well as Magnus Carlsen and Robert Fischer.

Niemann refused our offer to comment on these facts. A month ago, answering a similar question, he said that after being caught cheating online, he completely immersed himself in working on chess in order to prove his worth over the board in a live game.

The scandal began in early September at the prestigious Sinquefield Cup tournament in St. Louis, where Niemann beat Carlsen playing black, after which Carlsen refused to continue playing in the tournament. Although the champion did not make any accusations against Niemann at the time, the community interpreted Carlsen's actions as a protest.

A week later, the two players met again, this time in an online tournament, and Carlsen defiantly resigned on his second move. The next day, he finally publicly confirmed the reason for his unusual actions:

“I am convinced that Niemann cheated more often and for longer than he publicly claimed,” wrote Carlsen on September 26. “His progress in classical chess is unusual, and in the course of our game at the Sinquefeld Cup, I got the impression that he does not tense up and does not concentrate on playing even in critical positions, while outplaying me with black with an ease that only a few chess players are capable of.” .

Niemann replied that he used computer help in an online tournament with prizes when he was 12 years old, and at the age of 16 he used computer help in several random blitz games and considers this to be his main mistakes in life. He added that he never cheated in the games he streamed, and also over the board in classical chess.

The Chess.com report contradicts his statements. The table lists more than a hundred suspicious games, 25 of which were played on the stream. Niemann played the latest of these when he was 17 years old. Shortly thereafter, his account was frozen. The letter sent to Niemann mentions "outright cheating" to improve his rating, including in games against Russian top player Ian Nepomniachtchi, world vice-champion and current contender for the chess crown.

In 2020, Niemann confirmed the accusers were right in a telephone conversation with a senior site manager, Danny Rensch. The report includes screenshots of a Slack conversation where Rensch and Niemann discuss Niemann's possible return to the site, which is possible if he pleads guilty.

A month ago, Niemann wondered why he was not included in the Global Championship tournament with a prize pool of one million dollars. In a reply email, Rensch explained that the organizers still had concerns about Niemann's overt cheating in a number of tournaments with prizes, and they did not want to take risks. Rensch writes that Niemann's suspicious moves often coincided with switching windows on the computer, hinting that the player may have consulted the chess engine. Rensch is ready to provide statistical evidence that after switching windows, Niemann's moves became significantly stronger.

Player bans by Chess.com have always taken place behind closed doors, and the Niemann ban in 2020 was no exception. However, last month, following Niemann's vocal displeasure at not being included in the Global Championship, Chess.com decided to publicly share the reasons for the ban.

Among Chess.com's methods of catching cheaters is analysis to see if a player's moves match computer recommendations; studying the player's past games and compiling his "strength profile", monitoring the player's behavior during the game, including opening other windows; consultations with analyst grandmasters from the fair play department. So far, dozens of grandmasters have been banned from Chess.com, including four players from the world's top 100 (all of whom pleaded guilty).

Finding cheaters in classic over-the-board chess is a bigger challenge. The problem is that it doesn't take much for a cheating grandmaster to drastically improve his game. For an elite level player at a critical moment, a couple of subtle moves are enough to turn the tide of the game against the world champion. Therefore, if the cheater is not caught red-handed (for example, with a phone in the toilet or with an earpiece in his ear), it is very difficult to prove receipt of tips.

Niemann reached an Elo rating of 2300 in late 2015/early 2016. Obviously, he was a talented player. However, it took him two years to get to 2400, and then another two to get close to GM territory at 2500. He became a grandmaster in January 2021 at the age of 17, which is noticeably later than most other young players.

In the next 18 months, Niemann increased his rating by 180 points. This is the most dramatic rise of any of the leading young players in the world.

The report refers to Niemann's strange comment when analyzing the game he won against Carlsen after it ended. One of his statements revealed a surprising lack of understanding of the intricacies of the position in the game he had just won convincingly, which looked especially strange, given Niemann's statements about deep opening preparation.

In a personal conversation after the game, according to the report, Carlsen said that he played many games with talented young players and always noticed how hard they work at the board. Niemann, according to the world champion, played effortlessly.

The issue of Chess.com's possible involvement is also highlighted: the company is currently buying Carlsen's Play Magnus app for $83 million. The report states that although Carlsen's actions at the Sinckfeld Cup prompted further scrutiny of Niemann's games for cheating, Carlsen did not address them directly. Rensch previously said that Chess.com did not share the list of caught cheaters or the intricacies of the algorithm to catch them with anyone, including Carlsen.

During the Sinckfeld Cup, Niemann was asked to share his opinion on the effectiveness of Chess.com's anti-cheat methods.

“They're the best at catching cheaters in the world,” Niemann said.

With Niemann online, everything is clear, but offline, Chess.com experts are rather cautious. Growing faster than all competitors? Well, someone has to... Became a grandmaster at 17? Well, at the age of 10, Carlsen didn’t even reach the 4th category, when his competitors played at the level of kms. This is lyrics, and we need mathematics.

For mathematics, I had to turn to Brazil.

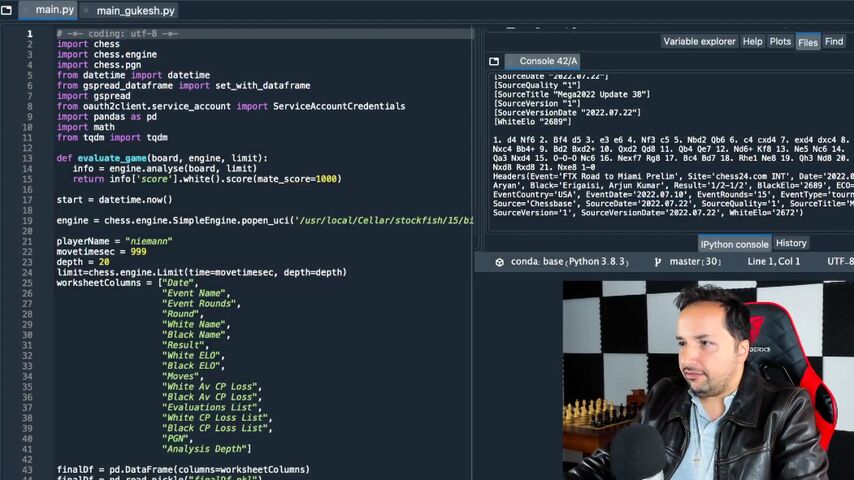

Hello to all chess lovers! My name is Rafael Leite, I live in Brazil and run one of the main YouTube channels with streams about chess. I want to offer you very strong evidence of a scam by Hans Niemann that started in 2018. For the past few weeks I have been working hard trying to shed light on this problem using science.

A little bit about yourself. I have been playing chess since the age of 14. My rating on Chess.com is around 2200, which is a solid amateur. I have been reviewing everything related to chess since 2018. I am also a programmer, developer and data scientist. I'll try to use all these skills to sort out the Hans Niemann fraud scandal. I must say right away that I had no prejudice against Niemann, I was just looking for the truth.

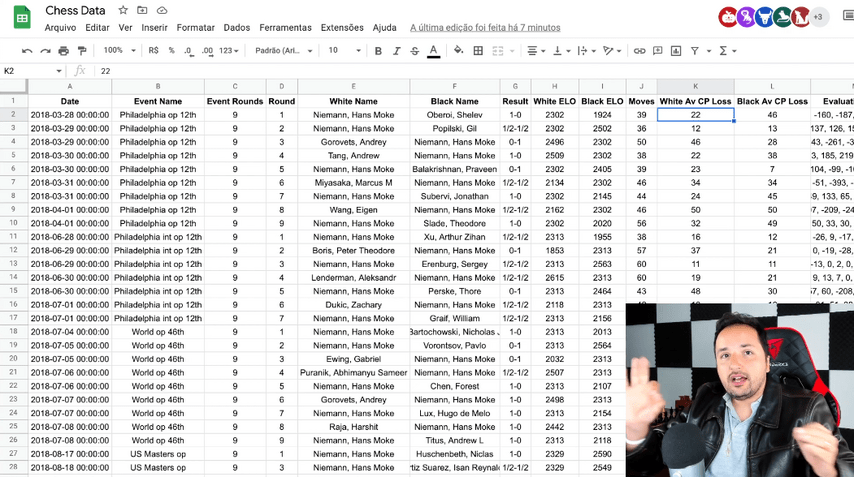

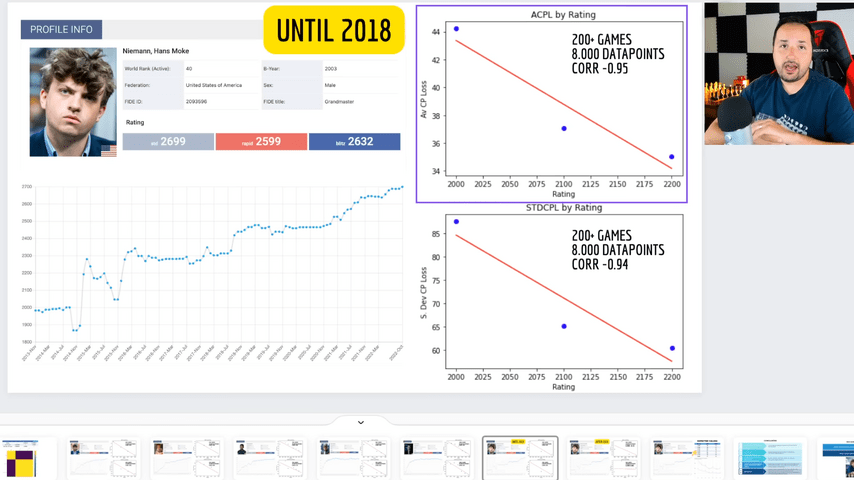

I wrote a script (and posted it on GitHub) that allows you to compare all moves in all games of a certain chess player with the best move offered by the world's strongest chess program, and calculates the difference between them in hundredths of a pawn. A person almost never (except for unique cases) can make a move stronger than a computer, the maximum is to repeat his choice. So for each game we calculate the average loss of centipawns and the standard deviation.

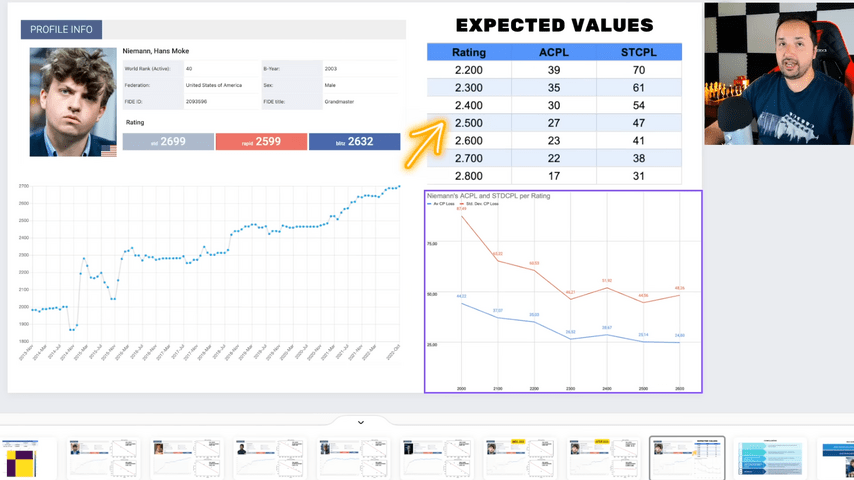

After counting all the games, I decomposed them into periods during which the player had a rating in a certain range – from 2200 to 2300, from 2300 to 2400, and so on, after which I calculated the average CP loss for each cohort and the standard deviation. What does it give? There is a strong (99%) inverse correlation between the average CP loss and a player's rating: the stronger a player plays, the closer his moves are to ideal ones. Logically. There is an equally strong correlation between a player's strength and the standard deviation in CP loss: top chess players are not only very strong, but also very stable.

Of course, one game means nothing: an amateur can play a great game, and grandmasters have bad days, but there are no exceptions to this rule at a distance.

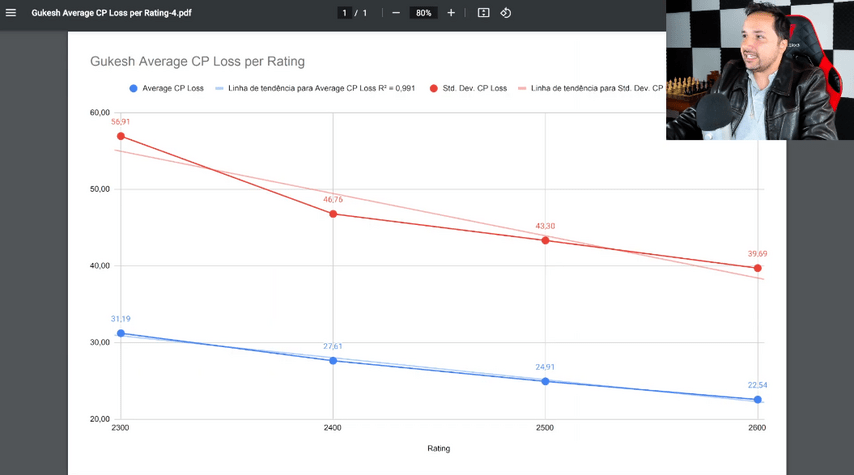

Let's look at the data of two chess players – Gukesh, a young star from India, and Hans Niemann.

Gukesh, when his rating was between 2300 and 2400, lost an average of 31.19 centipawns per move. Strengthening to 2400-2500, he made progress in the quality of the game and lost 27.61 centipawns; four percentage points is a very significant improvement in the game.

Even more precisely, he played in the interval 2500-2600 – 24.91 centipawns, and when he became a super grandmaster, having gone from 2600 to 2700, he removed another two and a half percentage points.

The standard deviation also steadily decreased from level to level – his game improved and became more stable. Logically.

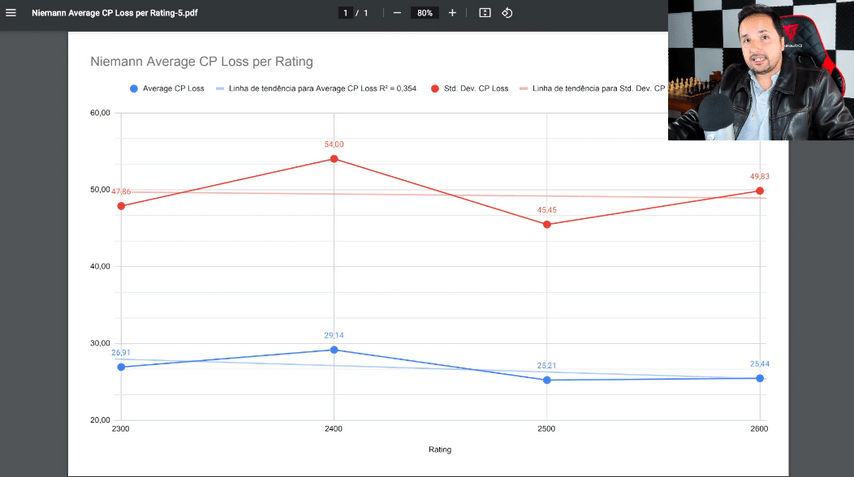

Now let's look at Hans Niemann's data.

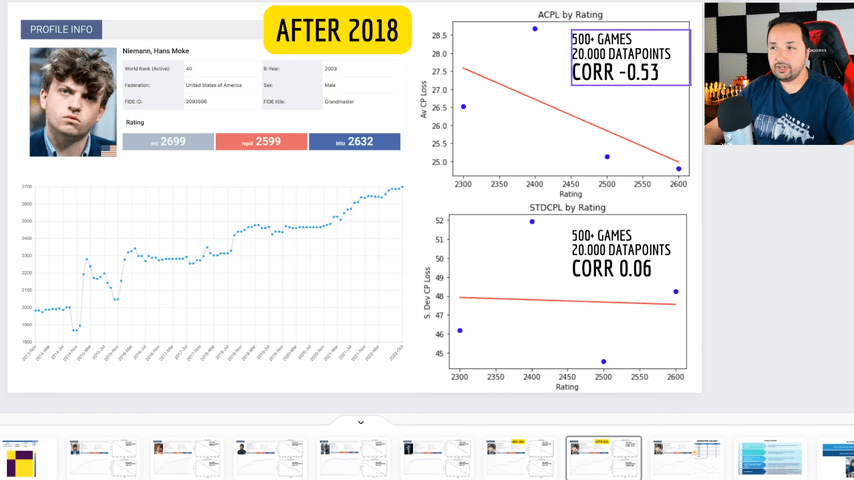

Already at 2300, his average centipawn loss was at an impressive 26.91, and on the way from 2300 to 2700, that figure only changed by one percentage point. Okay, one and a half. At 2700, he loses 25.44 centipawns every move.

It's very, very, very, very strange.

What do these numbers say? One morning, Hans Niemann, a young talent with a rating of 2300, woke up and played around the strength of Magnus Carlsen. And it hasn't gotten any better since then! Note the flat lines – both the mean loss and the standard deviation are surprisingly stable over the years. No difference! He plays at the same level.

In the coming days, I will calculate how the curves of other players behave, but anyone can check my data, the script on GitHub is open to everyone. In the meantime, based on the results obtained, I am inclined to believe that Hans Niemann has been cheating in offline games since at least 2018.

Files:

https://github.com/rafaelvleite/centipawn_loss_calculator

https://github.com/rafaelvleite/fide_crawler

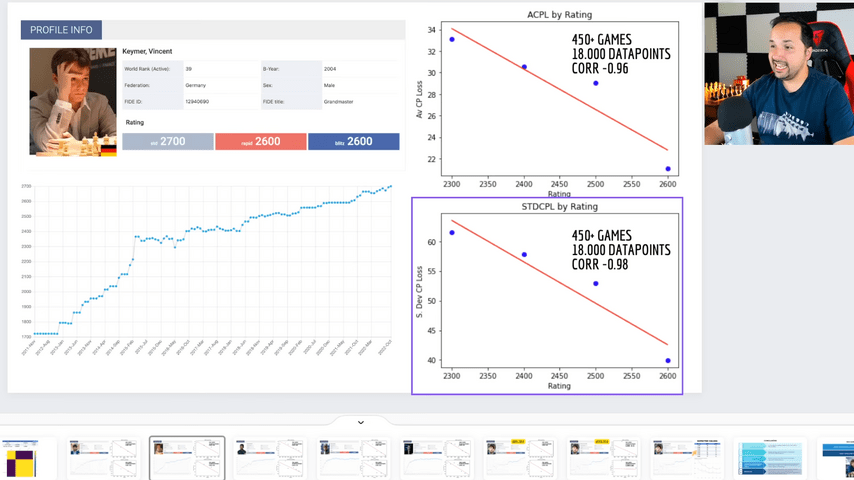

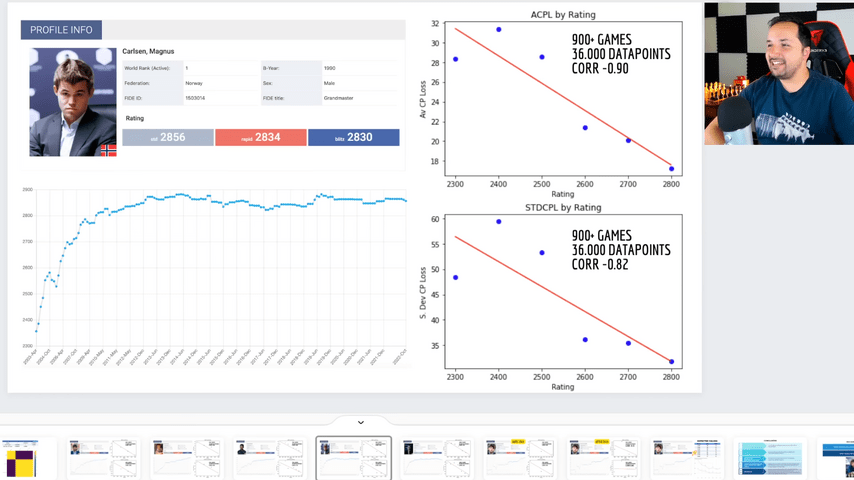

The day before yesterday, Rafael Leite posted another video in which he added data from a whole group of other strong players and showed the correlation between the average loss of centipawns, standard deviation and the strength of their game. As expected, the Niemann line and correlations remained unique.

Young talent from Germany Vincent Keimer.

Magnus Carlsen:

Hans Niemann until 2018:

Hans Niemann after 2018:

Hans Niemann's average loss of centipawns has been between 2500 and 2600 for many years.

How did he manage to raise his rating to almost 2700?

The answer seems quite obvious.