A couple of weeks ago, Stu Ungar's daughter Stephanie tweeted an article about her father written back in 1999 by American journalist Steve Fishman.

“What a pleasure it is to read a text written by a professional. There were so many articles, documentaries and feature films where everyone was wrong. I am very grateful to the author who made such an effort to tell the truth.”

The article was reposted with laudatory comments by Eric Seidel and Phil Hellmuth. On the anniversary of Ungar's death, the GipsyTeam editors publish it with minor edits.

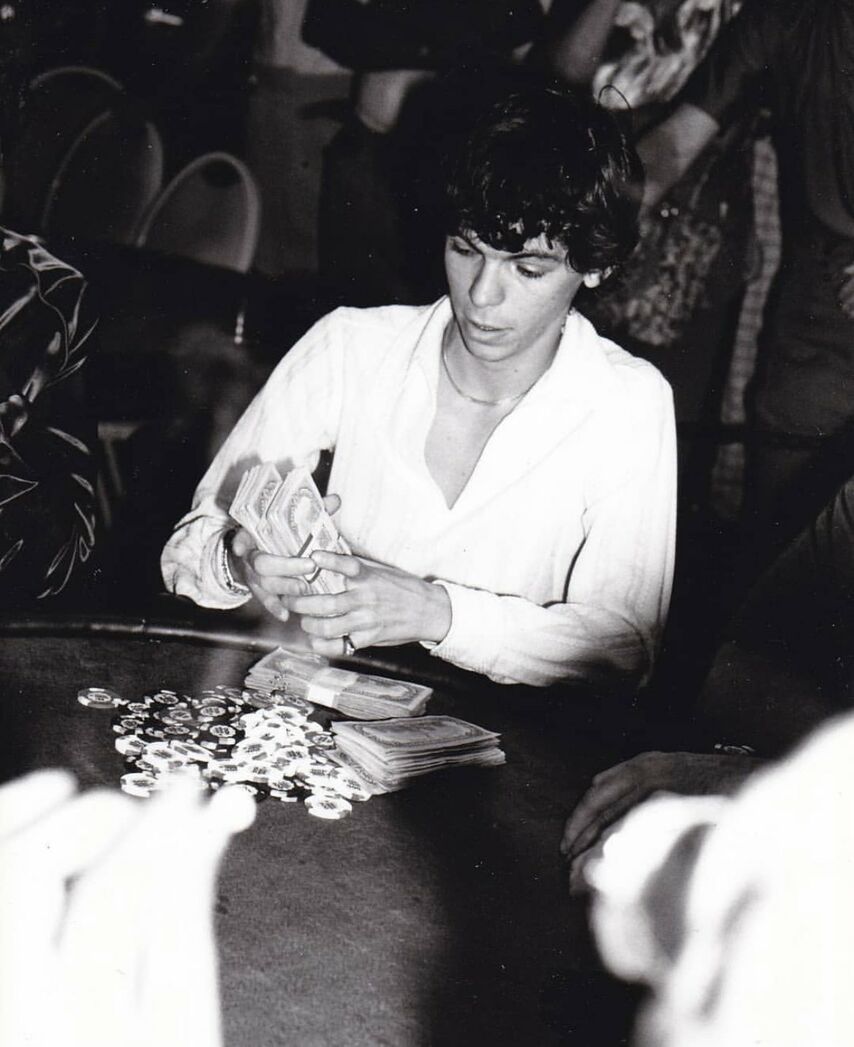

The air in Las Vegas is thick and damn hot. It's 38 degrees outside and the fans in the stands look lethargic. But then a man in a suit and tie appears, followed by two armed guards. They go up to a small air-conditioned stage where there is a poker table. A man dumps the contents of a cardboard box onto a green cloth: a million in hundred-dollar bills. People in the stands immediately perk up – either from the sight of money, or from the thought that one of the two players remaining in the tournament will take all this wealth home.

One of the finalists is John Stremp, owner of the Treasure Island casino. “Well, when you have a job, and you sit and play, you are not afraid of anything,” one of the rivals had teased him the day before. "Yeah, trust me," Stremp replied sullenly. But the crowd in the stands did not come to cheer for him. All eyes are on the other finalist – the one who, in his 40s, has never worked anywhere. His name is Stu Ungar, a New Yorker born into a bookmaker's family and raised among gangsters. The one who in the underground clubs of Manhattan was once called the "Mozart of the map world."

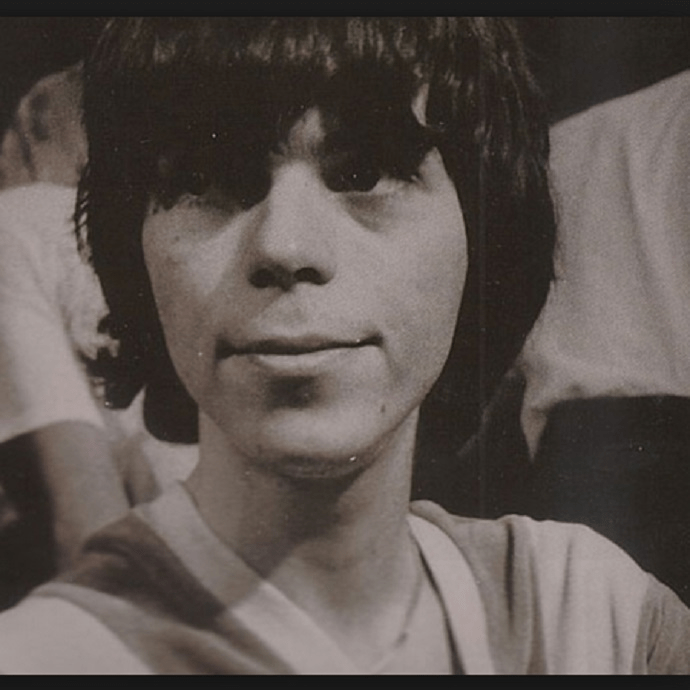

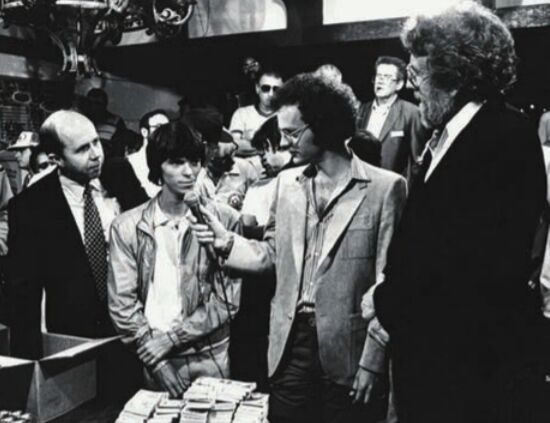

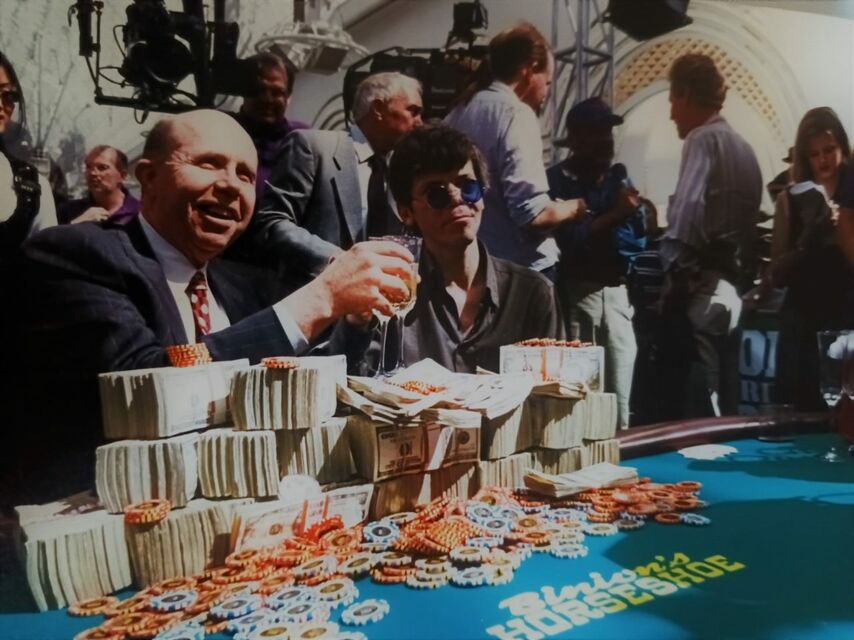

Stu looks at the piles of cash on the table through blue glasses that barely stay on the very tip of his cocaine-burned nose. He has already won this tournament twice, the last time – 16 years ago. “I forgot how cool it is when everyone comes up to shake your hand,” he tells an ESPN reporter. He speaks, however, indistinctly and crumples words, but no one seems to pay attention to this. When asked about plans for heads-up, Stu replies, deadpan: "I don't think there's anyone on the planet who can beat me."

The time for decisive winner is fast approaching. Stu lifts one of the cards and looks at it for a long time, as if asking – "well, won't you let me down, will you?". Then he raises his eyes to the sky and silently sits like that for a whole minute. And finally declares all-in with , Stremp calls all chips with , he's still ahead on the turn – but that's not enough. Stu becomes a three-time World Series Main Event champion. When giving his winners interview, he cannot contain his emotions, shaking and stuttering. “If anyone has beaten me in this life, it’s only me,” Stu takes out a crumpled photograph of his daughter and pushes it in to the camera lens. “Me and my bad habits. But when I sit down at the table, I know that no one can beat me. Nobody".

The audience could not see much, but managed to create a good picture for television

Ungar will go on to spend the million dollars in prize money in just 4 months. And soon he will leave this world himself.

Today, the house at 118 Second Avenue houses a candy store. But when Stu Ungar was a teenager, there was a Fox's Corner bar – a place for gangsters and gamblers. In the sixties there were no lotteries, no legal sports betting, no Atlantic City. New York was then a paradise for gamblers: there was a bookie in every bar, there was an underground game of cards on every corner. Stu's father, Isidor Ungar, looked no different from other respectable Jews of that time. It was impossible to assume that in fact the manager of the Fox's Corner bar was a large underground bookmaker, a big man in the world of illegal gambling named Ido.

118 Second Avenue, New York

His father would sometimes bring little Stu to the bar to proudly show off his precocious kid to friends and associates. Magnificent memory, amazing ability in mathematics – he studied so well at school that he was even allowed to skip one of the primary classes. To prevent the talented guy from constantly hanging out in the bar, his father sent him every summer with his mother to a resort in North Carolina. Stu liked being outdoors: one of the waiters later recalled that the little mischievous man had plenty of energy. Stu himself noted another important aspect of these trips: “I constantly looked over my mother’s shoulder when she played gin with her friends. I started noticing mistakes at the age of 8. Soon Stu himself began to play – with the waiters on their tips.

On September 8, 1966, my father held a bar mitzvah for Stu. There were too many mafiosi among the guests – in particular, Victor Romano from the Genovese clan came to congratulate the family. The guests gave Stu money, which he quickly lost at cards. At the same time, he increasingly began to skip classes: 13-year-old Ungar put on a ridiculous cowboy hat and went somewhere to play. One of his regular opponents later recalled that, despite his idiotic appearance, he almost always won. Soon, Stu's father died of a heart attack in the bed of his mistress – and there was no one to look after the teenager. He dropped out of school before finishing tenth grade.

Around the same time, Stu apparently stopped growing up: he remained forever 45-kilogram, short, awkward, with long arms and a funny nose. They openly laughed at him and called him a "monkey". At the same time, he was also hyperactive: he did not walk, but rushed forward, did not speak – but chattered so that the words formed into a long, illegible machine-gun burst. “He looked like a little chihuahua,” recalls the organizer of the game, which often included Stu’s mother. From the age of 14, her son also played there.

Ungar was an unusual teenager not only outside, but also inside. The ridiculous appearance and jerky manners only emphasized the other side of his personality – genius. “They say I have an eidetic memory,” Stu shrugged. “If you ask me what the game was like 3 days ago, I will remember all the cards and all the hands. It's a little disturbing." But a phenomenal memory was not his only gift: playing gin, he guessed the hands of opponents with amazing accuracy.

When Ungar was 16, he first came to Teddy Price – one of the most famous gamblers in New York, who was arrested more than once for cheating. Price did not even immediately understand what was happening – he thought that in front of him was the son of one of the players. “He holds out his hand to me and says, they say, how much is the game? I answer – let's play whatever you say, son, ”Price later recalled. “We started playing for $500 a game. I lost $1,500 and I'm done." Price soon became Ungar's friend and constant companion.

By the age of 17, Stu was already an experienced gambler. Every day he dangled from one underground club to another, slithering through unmarked doors like a thin shadow. Each had its own games: Italians loved ziganet, Arabs – barbott, Jews from Eastern Europe – Klaberjass, Greeks – rummy and konkan. Stu played with everyone and everything – or found opponents for gin and pinnacle.

“He stuffed his pockets with money, and then dragged them to the races,” says Teddy Price. “And he always lost everything there, down to the last cent. Massage parlors were his other passion. If there were, say, 58 of them in New York, then Stu knew all 58 addresses. Everywhere he was a regular customer: he took a Cadillac from me, came to one of them, and a woman’s cry was immediately heard: “Oh, Stu is back!”

And then, when he has a good rest and lost everything at the hippodrome, he returns to the game. Money meant nothing to him at all. He only wanted to play and bet. If he was sitting and waiting for a seat at the table, and you called him for dinner, he would rather give you $5,000 than get up from his chair.

In one of the clubs, he once met an old friend of his father – the mafioso Victor Romano, who was at his bar mitzvah. Romano took the guy under his wing and since then often repeated that Stu was like a son to him. A strange couple – a 60-year-old gangster who spent half his life in prison, and an 18-year-old dystrophic gambler – but they became very close. So Ungar got into the world of big bookmakers, rich mafiosi, thieves and bandits. He began to play gin with them and received a serious bankroll from Romano.

A gambler nicknamed the Bronx, one of New York's top gin specialists, muttered irritably "I'll beat him anyway" as he lost again and again. Gamblers flew in from Canada and Vegas just to fight Stu. He arrogantly offered to each of them to bet as much as they wanted – Romano was ready to play for any money. Victor himself was a talented gambler with a phenomenal memory. While in prison, he published a series of articles about bridge in Bridge World magazine, and when he was released, he quoted the interpretation of any term from Webster's dictionary on a dare – he knew it by heart. Every Sunday, he and Stu would sit down to go over the games of gin they had played all week, rebuilding them from memory.

At the age of 20, Ungar began dating Madeleine Wheeler, a pretty young waitress who served tea in one of the clubs. Soon he moved from his mother to her. Romano was very happy: he had been telling Stu for a long time that it was time to settle down, start a family, start dressing neater, stop losing money on bets and turn cards into a stable source of income.

Soon, Victor introduced Stu to Gus Franco, the head of the Romano mafia clan. The news of this quickly spread around New York: now Ungar has become part of the "family". This delighted him: firstly, he was a fan of mafia aesthetics and was very happy when some bandits called him Meyer (after the famous Jewish gangster Meyer Lansky). Secondly, it provided protection from collectors. The Romano family made it clear to the whole city that Stu now needs to turn to Victor Romano's nephew, a street fighter known for his cruelty, about Stu's debts. There were few people who wanted to talk to him.

But even under these conditions, Ungar managed to get into trouble. One weekend, he lost big to a representative of another, no less respected mafia family. On Sunday, Stu called Price:

''We're going to California tomorrow.''

"What are we to do there?"

''There is nothing. But I lost $60,000 yesterday, I don't have a cent. I think they will kill me.''

Romano had a call from California. He agreed that no one will touch Stu, provided that he goes to Vegas, earns money there and returns everything. So, Ungar ended up in the City of Sins.

In the seventies, Vegas was a deserted place where mostly gamblers went – the population there was at most 150,000 people. And also Hollywood stars, all kinds of circus performers, magicians and singers – and, of course, mafiosi in jackets and ties, including Tony "The Ant" Spilotro. “Have you heard of him?” Stu whispered breathlessly to his interlocutors. Joe Pesci then played him in the movie "Casino". Ungar quickly got used to Vegas – and entered any casino as if he owned it. “Stu always acted like he was a big shot,” his mother-in-law later recalled. “What was his name worth! Step aside, the great Stu Ungar is coming."

A kid-like guy acting like a gangster is a hilarious sight. But the laughter subsided when he sat down at the table. Danny Robinson was considered the best gin player in the city at that time – until 22-year-old Stu arrived there. On the very first night, Danny lost $100,000 to the new kid. “He just knew something about this game that no one else knew. The greatest gin player ever to walk the earth,” Danny later said in an interview.

Soon Stu called his girlfriend Madeleine. He said that he paid off his debts, and there was another million dollars in cash in the safe. She moved to Vegas, they got married, had a daughter. Romano was at the wedding, Ungar paid for his business class flight. Without Stu's support, his club in New York had closed by then, and his "family" had suspended him from business due to health problems. So, an already weak and broken old man flew in to congratulate Ungar – he died just a few days later.

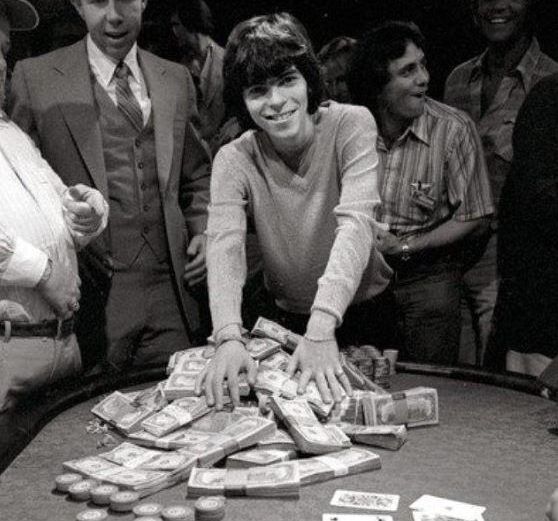

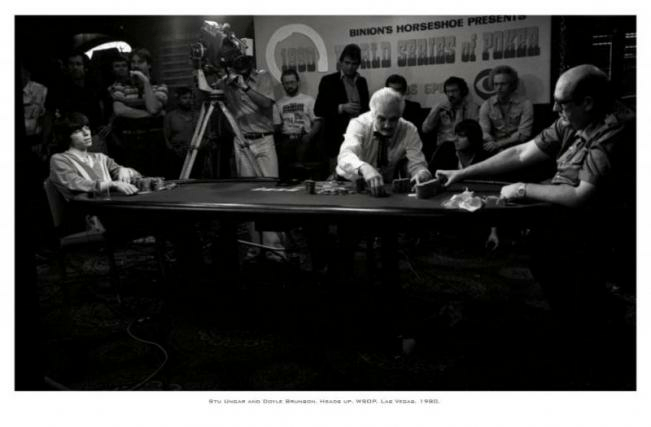

But Romano managed to see the first poker victory of his beloved protégé. Stu decided to try out a new game at the World Series of Poker and immediately won in heads-up against Doyle Brunson in the Main Event. He received $365,000 and a bracelet, which he later gave to his nephew Romano, the same street fighter that was used to scare his creditors in New York. Soon Teddy Price also moved to Vegas. Just a couple of years earlier, Ungar had called him, afraid of being killed due to debt, and now he was meeting him as an old friend, a rich man, who was admiringly called the "prince of Las Vegas."

Heads-up between Ungar and Brunson

Madeleine meanwhile made the family nest. She told Stu that she wanted to buy a house, to which he calmly replied: "Go and buy one." The realtor took the deposit from Ungar in the casino: he counted out $40,000 in cash for him right at the table. There was a swimming pool in the yard, and 6 TVs inside the house (Stu insisted on this). In those years he no longer looked as ridiculous as before: his wife ordered Versace suits for him, he had a haircut from a personal hairdresser and had a manicure in a salon. He was often asked in interviews if wealth makes you happy. “Yes, I seem to be happy with everything!” Stu laughed. "I like spending money."

He really enjoyed spending money, and he didn't care about it either. When he won the WSOP Main Event again in 1981 for $375,000 and the press asked what he would do with the winnings, he muttered, "I'll lose everything." And when asked to repeat it on camera, he squared his shoulders, smiled and said: “I’ll put it in the bank and leave it for my daughter, what else?” And then he laughed.

Money for Stu was only buy-ins – in any conceivable game. He once played ping-pong for $50,000 a game. Tossed coins for $1,000 per flip. He organized competitions where people played billiards with broom handles, and golf with hammers. “It’s embarrassing to talk about some of the things I bet on,” Stu said later. And Bob Stupak once recalled how Stu won $10,000 from him in poker, and then lost everything by throwing chips at the wall to see who could get closest right next to the cashier.

And then Ungar discovered golf. He had no experience, they did not play golf in New York. But in Vegas, the sport was the favorite pastime of dozens of rich people, and for Stu, the thought that he was missing something was unbearable. He demanded that one of his friends take him to a private club – and two hours later he was $80,000 poorer. He played terribly – but he wanted to compete so much that experienced golfers even allowed him to put pegs under the balls to make it more convenient to hit.

“Once we played for $40,000,” Chip Reese said. “He hit and the ball went into a deep creek. I decided that was everything, the game was over – and then Stu calmly took a 30-centimeter peg from his bag, took off his shoes and socks and climbed into the water.

Despite minor annoyances, Ungar's life in Vegas was happy. He liked to play and live among gamblers. Las Vegas in the eighties represented everything that Stu loved so much – as if he had finally begun a real life, which he always wanted. At the same time, he completely ignored all technology: he never approached computers, did not use checks or credit cards – he simply walked around with pockets full of wads of dollars. He didn't even check his mail much, so sometimes he came home and found that the electricity had been cut off for non-payment. “This guy was straight out of the jungle,” said Jack Binion, former owner of the Horseshoe Casino.

"Jungle Boy" was about electricity bills: he played for days and nights on end. When he wanted to sleep too much, he snorted cocaine to cheer him up. And when even cocaine didn’t help, he could pass out at the table – and his friends carried him to the hotel room right on the chair. He and his partners played the most expensive games in Las Vegas – in this city then you could always find a good game.

“Once we played for a very long time,” recalled Mickey Appleman. “And then one guy asked: “Listen, what is happening in the rest of the world right now?”. And the other answered him: “Do you care? We live in paradise."

By the mid-80s, Stu had made a fortune. “I saw him win a million in an evening a couple of times,” says Mike Sexton. “His big victories were unmissable – he threw big parties. Once, after winning $800,000, Stu hired a prostitute and gave her a $30,000 tip.”

Despite the huge winnings, close friends knew that in reality everything was not so rosy – Ungar's big money both appeared and disappeared without a trace. The meaning of his life was the action: and when there was none, he created the action himself – even if it was obviously unprofitable.

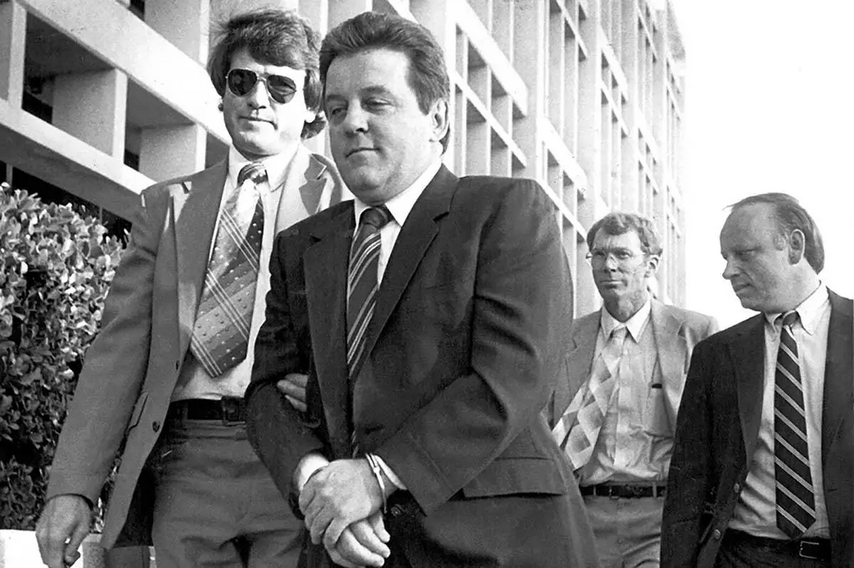

Most of the money was spent on sports betting. He himself often repeated that there was no point in it, that it was all blind luck – but he could not control himself. He once lost $1 million over a weekend, mostly to Tony Spilotro. Tony's reputation was so-so: at one time he was arrested for the murder of 20 people, but they could not prove anything. And although Stu proudly called Spilotro his friend, he was definitely not the kind of lender who could not be paid for a long time.

Arrest of Tony Spilotro

Failure quickly drove Stu into depression. “If you could measure the joy of winning and the frustration of losing, the second would be disproportionately greater,” complained Stu. He was so depressed that the doctor prescribed him lithium as an antidepressant. But friends knew: only a game could get Ungar out of such a state – and as expensive as possible.

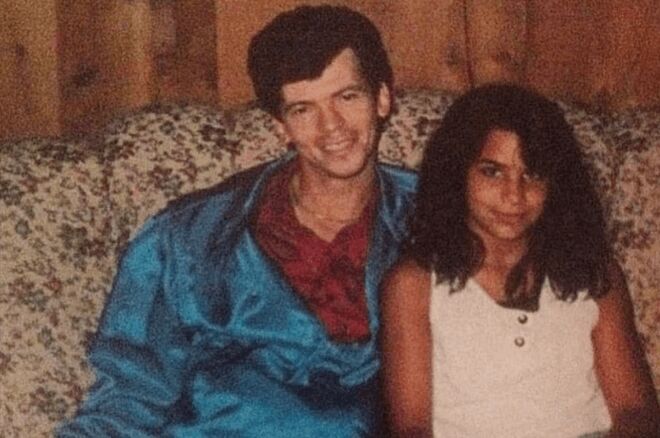

But there was no longer enough money or energy for expensive games. His health failed – his nose was completely burned by cocaine. Stu had an operation to restoreit – but, according to the story of his wife's brother, just a couple of hours after leaving the hospital, Stu was already sniffing another line. In 1989, his wife took their daughter and left Vegas. “The drugs destroyed our marriage,” Madeleine later said in an interview.

Stu with his daughter

By the mid-nineties, the house also went under the hammer – Ungar needed money. He settled in a small room in the house of a friend who put up only one condition – no alcohol or drugs. Stu kept the agreement, but did not know how to live in the new reality. From childhood, he was a gambling star: he was admired, everyone forgave him, everything was done for him. He didn't even know how to run the dishwasher – and he certainly wasn't able to get a job. He tried to devote time to his daughter, but even then everything was not easy. “He loved her very much,” said one of the friends. “But he had no idea how to be a father to her.”

In May 1997, the next World Series began. On one of the walls of the casino was a huge photo of Stu – young, in a gold satin jacket, with a mischievous smile on his face. Apart from friends, few people knew that that tournament 16 years ago was the last one that Ungar won – and in 1997, even scraping together $10,000 for a buy-in became an insoluble problem for him. Billy Baxter helped: “God bless you, I had worse investments,” he said, giving Stu cash.

He was the last to register in the tournament out of 312 participants – the main then updated the attendance record. Stu looked terrible: a tightened belt on a haggard body, sparse bangs with gray hair, large round blue glasses that barely concealed a nose destroyed by cocaine. But at the table, he again became himself, without fear, making bet after bet. “For some reason everyone thinks I have the nuts,” he laughed, raking in mountains of chips.

And there's a million dollars in cash in front of Stu. "Man, I saved your life," exclaimed a pleased Baxter when he received his share. Ungar rented an apartment and moved out from his friend's place. He even decided to renew his long-expired driver's license. And when the Department of Transportation asked him to show his ID, he yelled: “Don't you see? I'm Stu Ungar!" Everything seemed to be back to normal.

But in the 20 years that Ungar spent in Las Vegas, the city has changed a lot. From a deserted and mysterious paradise for gamblers, it has turned into the capital of holidays and vices. Now families come here on vacation. Amusement parks are open. A huge sphinx stood in the middle of the city, and copies of New York skyscrapers stuck around. The casino where Stu played was closed – in its place was the chic Bellagio hotel. There were no gangsters inside, and Tony Spilotro had been killed long ago. Vegas was quickly becoming part of corporate America—a city of businessmen, not adventurers.

And there was no place for Ungar in this renewed Vegas: Stu turned into an urban legend about how one day a guy who was heavily in debt came from New York, got up to $25 million, and then lost everything. Well, the hero of this story himself wandered in the afternoon to Bellagio, where old friends were already waiting for him. They were still playing, but more to pass the time than for profit. Bulky Doyle Brunson hobbled over to the table, leaning heavily on his cane. Danny Robinson fell into religion, although he continued to earn a living ("I received a blessing. If I play honestly and responsibly, then this is not a sin, but an ordinary job"). Chip Reese was largely retired, mainly because there weren't many big games left.

Out of boredom, Stu reverted to old habits. One day he won $194,000 betting on baseball, the next (as he knew he would) he was losing that money, and the same amount on top. Well, drug dealers quickly surrounded a promising client, having read about his latest victory in the newspapers. 4 months later, Ungar again moved into a little room in a friend's apartment: there was nothing left to pay for the rent of the apartment. After that, he was seen several times more confusedly wandering around the Bellagio – a lost, stoned ragamuffin. Sometimes he even had money with him, but he was no longer drawn to the tables – gambling and the new emasculated look of his beloved city began to infuriate him.

On Friday, November 20, 1998, Stu booked a room at the Oasis on the edge of the Strip, a shabby hotel with hourly rates, dirty mirrors, and stacks of adult videotapes on the bedside tables. The manager came to see him the next day. Stu, without getting out of bed, paid another day in advance. “When I left, he complained that he was cold and asked to close the window,” the hotel employee later recalled. "But the window was already closed." A day later, the manager went up to Stu's room again, but no one answered the knock. 45-year-old Stu Ungar was found dead in bed: he was dressed, there were no drugs in his pockets – only $800. The TV was off.

More than a hundred gamblers came to his funeral on the eve of Thanksgiving – a holiday that Stu once loved to spend in the company of Victor Romano. The rabbi mentioned in his speech that Ungar had been killed by a “disease,” as he called drugs. And although they, of course, played a role, the toxicological examination showed that Ungar did not die from an overdose. There were versions about asthma and heart disease, but the exact cause of death remained unknown.

Just two days before his death, Stu made a deal with an old friend, Bob Stupak, about backing. Bob promised to buy him into a big $370,000 guaranteed tournament at the Taj Mahal Casino in Atlantic City in December.

“How are we going to get to Atlantic City?” he asked Bob.

“How would you like to go?” Stupak asked.

"Let's fly business class," Stu smiled.